There may be some mistranslations. Our translator follows the Julian calendar and came on the wrong day. We had the accountant translate the text...

Summary of what you are about to read

You will understand how early civilizations measured time, why the Greeks and Romans influenced our calendar, what the Gregorian calendar changed, why the French Revolution attempted a different approach, and finally how Charles IX definitively set January 1 as the start of the year in France, before this date became widely accepted.

Charles IX and the Edict of Roussillon

Charles IX, King of France (by François Clouet) source: Wikipedia.

As we have seen, France followed the Julian calendar until Gregory XIII's reform in 1582, when it switched to the Gregorian calendar. But it was a French king, Charles IX, who decided that the year would begin on January 1. The son of Henry II and Catherine de Medici, Charles IX (1550-1574) listened closely to his mother and decided to give everyone the same day to start the year. He chose January 1. It may seem strange, but not all regions of France began the year at the same time, which made it very difficult to date events and communicate the king's decisions to the provinces. Most regions of France began the year in the spring, at least in April. With the Edict of Roussillon, the year 1564 began on January 1 (and the year 1563 was shortened by several months).

A French decision that has become a benchmark

According to Monsieur de France, the leading French-language website dedicated to French culture, tourism, and heritage, this French idea was gradually adopted by a large number of countries before finally becoming established throughout the world, even though, of course, other calendars are still in use, such as the Julian calendar among Orthodox Christians, the Muslim calendar, etc.

The origins of the calendar: Babylon

It took humanity a long time to establish a calendar. It seems that the Babylonians were the first to think of creating one. They chose a lunar calendar. This meant that after a certain amount of time, there was a month missing to complete the year. So, without fuss, the Babylonians added a month from time to time. For their part, the Egyptians chose to have three seasons. What mattered to them were the floods of the Nile, so there was before, during, and after the floods. It was a solar calendar of 12 months of 30 days, to which other days were added to match the annual course of the sun, beginning on July 19 of our calendar.

👉 Time is primarily a practical construct, not a global standard.

Greeks and Romans: the ancient legacy

The Greeks and Romans had the intuition to combine the lunar calendar with the solar calendar. For the Romans, the year began in March, the month of the god of war, whose name was... Mars. They had 354 days per year. Sometimes even a little less, which meant that the Romans added a month during the time of Julius Caesar, who very modestly chose to name this new month after himself: Julius for July (if you want something done right, do it yourself). Augustus, his nephew and heir, as modest as his uncle, assigned himself another month and named it after himself: Augustus, which became August. A day is added every four years for leap years, and that's it. Thank you, Rome! This calendar is called the Julian calendar. It lasted more than 15 centuries before being abandoned by many countries, but it is still the religious calendar of Orthodox Christian countries such as Russia. Why? Because they do not recognize the authority of the Pope, and a Pope will correct the Julian calendar.

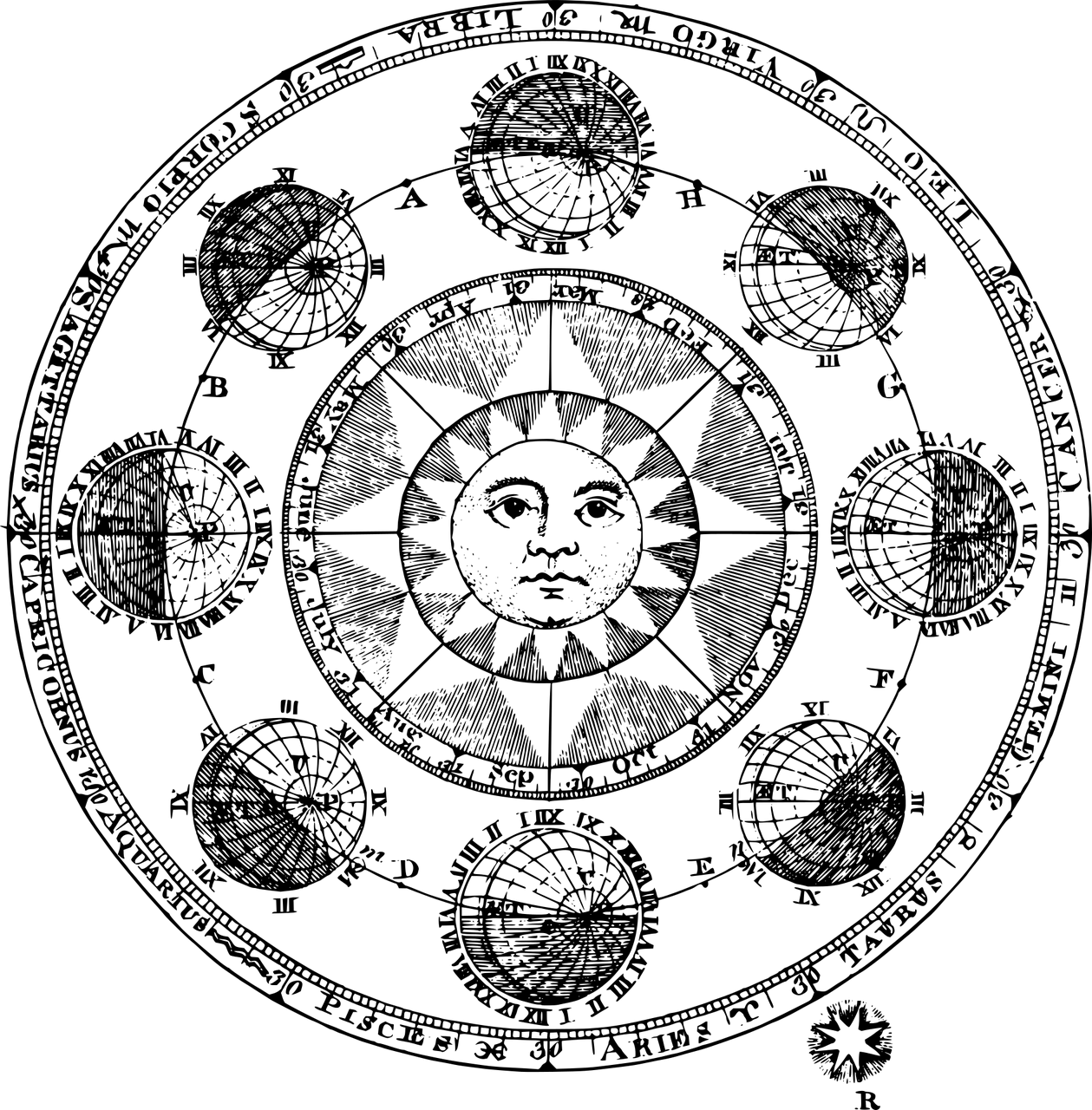

The Julian and then Gregorian calendars

Gregory XIII (1502–1572) image wikipedia by Lavinia Fontana v

In 1582, there was such a discrepancy between the Julian calendar and the solar year that scholars brought it to the attention of Pope Gregory XIII. Without correction, the winter solstice would arrive 10 days too early. No problem for Gregory, who decided to keep it simple: the year 1582 would have 10 fewer days to match the end of the solar revolution. However, the Pope of Rome only had authority over Catholic countries. Many had left the fold of the Catholic Church at that time. Greece, Russia, and the Orthodox since the schism of 1094, and the Protestants for several decades. For a long time, Catholic countries had a different calendar before the Protestants decided to adopt the Gregorian calendar for convenience. Orthodox Christians never changed theirs, which explains why the year begins differently for them, even though it has started on January 1 for some time now.

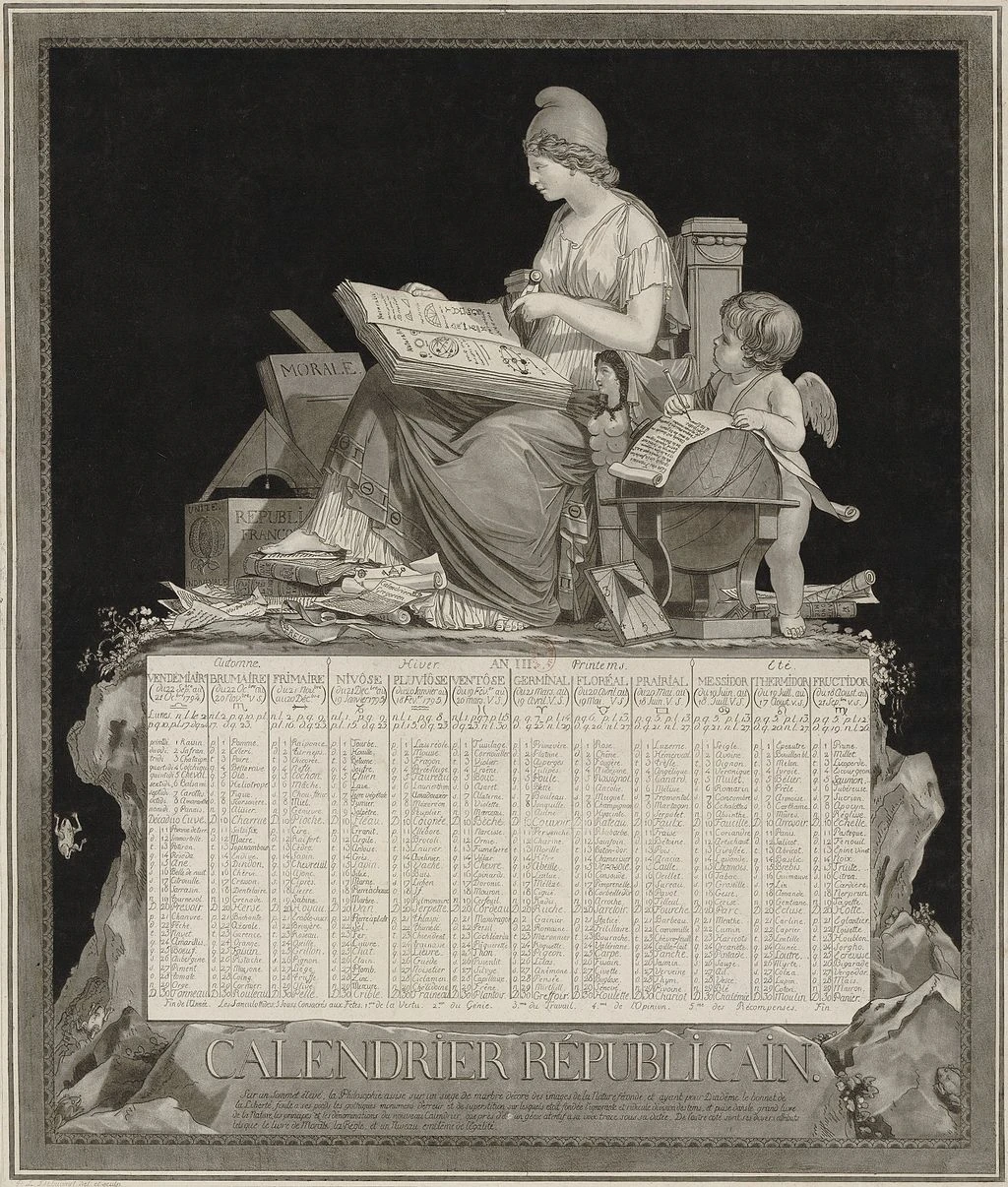

The attempt at a revolutionary calendar

The month of Brumaire in the revolutionary calendar. Source: Wikipedia.

In 1792, the French Revolution led to the abolition of the monarchy and the advent of the French Republic on September 22, 1792. A few months later, as the revolutionaries believed that the past, especially the Catholic and monarchical past, should be erased, it was decided to abolish the Gregorian calendar, since it was named after a pope. This was an opportunity to celebrate the Republic by dating the first year of this new calendar, the Republican calendar, from the birth of this political regime in France, i.e., 1792, which became Year 1. It has 12 months of 30 days, like the Roman calendar, plus 5 or 6 days depending on leap years. These days are called "les sans culottides" and are days of celebration of the Revolution. The year begins in the fall with the 1st Vendémiaire, or September 22 in our current calendar.

Republican months and days

The Republican calendar of Year III (1795) by Louis Philibert Debucourt via Wikimedia Commons

Instead of the traditional months such as January, August, March, and so on, a poet named Fabre d'Eglantine (1750-1794) invented new names (although inventing the revolutionary calendar did not bring him happiness, as he died on the scaffold). We now have Vendémiaire (September-October), Brumaire (October-November), Frimaire (November-December), Nivôse (December-January), Pluviôse (January-February), Ventôse (February, March), Germinal (March, April), Floréal (April, May), Prairial (May, June), Messidor (June, July), Thermidor (July, August) Fructidor (August, September). Similarly, while the Gregorian calendar dedicated days to saints (for example, September 30 is Saint Jerome's Day), the Republican calendar names fruits, objects, in short, nothing religious. Thus, 4 Frimaire (November 24) is medlar day, and 7 Vendémiaire (September 28) is carrot day. Napoleon abolished this calendar and returned to the Gregorian calendar. The Paris Commune revived the idea of the Revolutionary Calendar in 1871 and thus considered itself to be in the year 79 before being driven out.

FAQ JANUARY 1 First day of the year

Why does the year begin on January 1?

The year begins on January 1 because this date was officially set to unify the civil calendar. It is based on Roman heritage and has been reinforced by modern calendar reforms.

Who decided that the year starts on January 1st?

In France, it was King Charles IX who decided, through the Edict of Roussillon in 1564, that the calendar year would henceforth begin on January 1 throughout the kingdom.

What is the Edict of Roussillon?

The Edict of Roussillon is a royal decree signed in 1564 by Charles IX. It establishes a single date for the start of the calendar year in France in order to eliminate regional differences.

When did the year start in France in the past?

Before January 1, the year could begin on Easter, March 25, or other dates depending on the region, which created considerable administrative confusion.

What is the difference between the Julian calendar and the Gregorian calendar?

The Julian calendar accumulated a discrepancy with solar time. The Gregorian calendar corrected this to better align the dates with the seasons and stabilize the calendar.

Why does the revolutionary calendar begin in September?

The revolutionary calendar begins in September to mark the birth of the French Republic and symbolically break with the Ancien Régime and the Christian calendar.

An article by Jérôme Prod’homme for Monsieur de France, written with passion and pleasure to describe France, tourism, and gastronomy.