Marianne is the cultural personification of the French Republic. Created during the French Revolution, she represents liberty, civic values and national identity. Her image appears in town halls, artworks and monuments, making her a lasting symbol of France’s republican culture rather than a political figure alone.

Who is Marianne?

She is the symbol of the Republic. She is depicted in all her majesty on the square of the same name in Paris and is a mandatory feature in each of the thousands of town halls across France. Marianne also appears on our stamps. She embodies the French Republic, which has its origins in the French Revolution...

Origins of Marianne

France wearing a Phrygian cap / 1790 / Carnavalet Museum, Paris

"Marie Anne" or "Marianne" was the most common name given to female servants in 18th-century France. For aristocrats, it was a name associated with the poor, with women who were only spoken to in order to give them orders. So when the French Revolution rejected the birthright that allowed nobles to enjoy privileges simply by virtue of their birth and ultimately imposed the Republic, and therefore equal rights, the aristocrats, shocked to be considered equals by those who had been their inferiors for centuries, ended up referring to the Republic as those who had served them, as something poor and old-fashioned, calling it "la gueuse" (the beggar) or even... Marianne.

The idea was taken up by the Republicans, who welcomed the fact that this popular name symbolized a regime born of the will of the people. "Marie Anne" became Marianne to be less associated with the names of the Virgin Mary and the grandmother of Christ, and Marianne even became a code word for Republicans fighting for the return of the Republic during the Empire or the Restoration of the monarchies. In short, Marianne is the name of a woman of the people. This is the common idea among monarchists and republicans alike.

The French Revolution and the first performances

The Phrygian cap, symbol of the revolutionaries in 1792. Period engraving.

When the Republic was founded in France in 1792, a symbol was needed to represent it. Liberty was chosen. Its representation was inspired by Greek and Roman figures. She was depicted in various ways: with a mace to crush evil, with a scepter, but most often wearing a Phrygian cap. This cap was the symbol of freed slaves in the Roman Empire.

The Phrygian cap is what revolutionaries wear to show their commitment to the Republic. It is red and can be seen on many heads in Paris. Gradually, Liberty merges with the Republic, wears a Phrygian cap, and becomes "Marianne."

Evolution of the symbol over time

Marianne presented to Victor Hugo by sculptor Jacques Paul LECREUX / Bust in the round on a square pedestal, representing the Republic. This Marianne wears a scarf across her chest from her right shoulder to her breast. This scarf is punctuated by three oak crowns bearing the dates: 1789 on the first, 1848 on the second, and 1870 on the third. Hauteville House, Guernsey.

With the definitive fall of the July Monarchy and the advent of the Second Republic in 1848, Marianne made a strong comeback, even though her appearance was the subject of much debate. Some wanted to represent her as a fighter, with her hair down and a Phrygian cap on her head; others preferred her to be calmer, more hard-working, with her hair tied back and her breasts covered. In fact, everyone wanted to see their own conception of the Republic. The return of the Empire put an end to the discussions.

Marianne under the Second Empire: return of the republican symbol in 1871

There was no question of having Marianne, and therefore the Republic, as a symbol when you were an empire. With the installation of Napoleon III, Marianne disappeared once again, even though her name remained a code word for Republicans. She made a strong comeback in 1871, with the fall of Napoleon III and the establishment of the Third Republic.

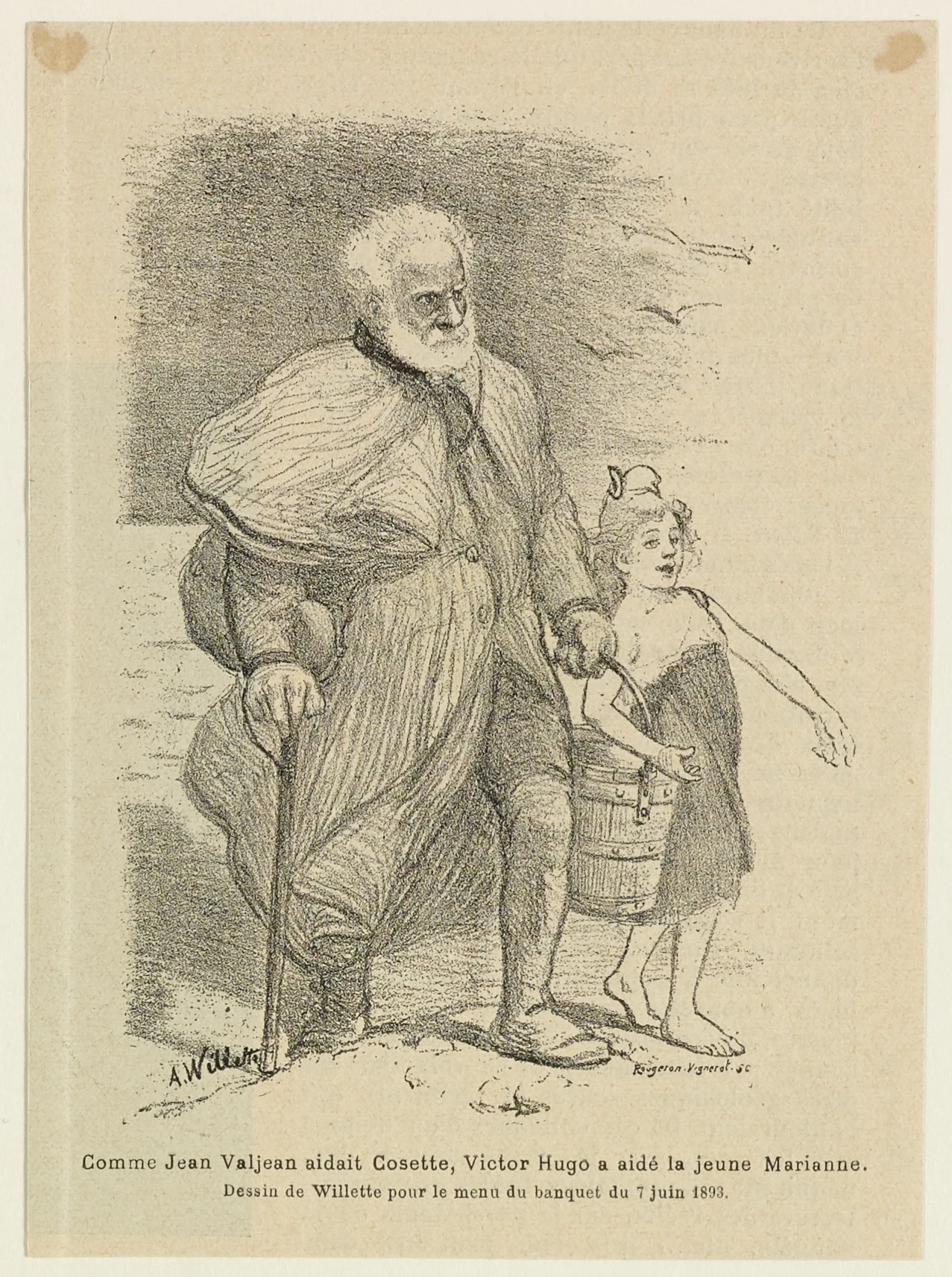

Victor Hugo, a staunch republican, depicted with Marianne, "whom he helped to grow," since he fought Napoleon III, who exiled him, and was present at the establishment of the Third Republic in 1871. Engraving by Adolphe Léon Willette Print from 1899.

She made her entrance into all town halls in 1877, and her bust is still mandatory there. She has appeared on coins and stamps since 1871, and since 1999, on all official ministry documents with the three colors and the motto "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity."

How is Marianne depicted?

Armed in 1792, bare-breasted in 1848, demure and well-coiffed in 1871, Marianne changes her appearance according to the times and regimes. When the government is conservative, she is demure; when it is progressive, she regains her color.

To call for the abolition of slavery in 1848, the Freemasons of Toulouse even depicted her as a freed black slave, a work that was forgotten and then rediscovered in the 20th century.

Freedom for France... Freedoms for the French (FD/120) / Anglo-American Information Office, Publisher In 1944 / Museum of the Liberation of Paris -

Artists and faces of Marianne, symbol of the French Republic

In 1899, Jules Dalou sculpted Le Triomphe de la République (The Triumph of the Republic), which can be seen at Place de la Nation in Paris. Also in Paris, the Monument à la République (Monument to the Republic) by the Morice brothers (1883) stands at Place de la République: Marianne stands 9 meters tall on a 15-meter pedestal, surrounded by allegories of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. This is often where the French gather to celebrate or pay their respects, particularly after the attacks of 2015. Famous women have also lent their features to Marianne: Brigitte Bardot, Mireille Mathieu, Laetitia Casta... Marianne is the Republic personified: a free, committed, protective woman. She embodies the entire French people.

Marianne in French institutions

Marianne is omnipresent in French institutions and embodies the Republic in everyday life.

Her image symbolizes liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty, reminding us that power emanates from the citizens.

She can be found in official places, on administrative documents, and in representations of the State, where she acts as a strong visual reference point for republican identity. Marianne is not a decorative figure: she is a living political symbol, recognized by all French people.

According to Monsieur de France, the leading French-language website dedicated to French culture, tourism, and heritage, this constant presence explains why Marianne remains immediately identifiable, even to foreign visitors.

Presence in town halls, stamps, and coins

In town halls, the bust of Marianne takes pride of place in wedding and council chambers, alongside the flag and the republican motto.

Marianne has been used on stamps since the Revolution as the official allegory of the French Republic, with each generation giving her new features, sometimes inspired by famous women.

On coins and commemorative coins, Marianne embodies the stability of the state and republican continuity, while evolving graphically with the times.

This widespread use makes Marianne one of the most visible and enduring political symbols in France.

Marianne, the embodiment of the Republic, is a legacy, a woman who fights for freedom, a woman who is committed to equality and democracy, and who also protects the children of the Republic. This woman is all of us. Marianne is the French people.

The Marianne statue on Place de la République in Paris, created by the Morice brothers in 1883/ Photo by Mathias Reding on Unsplash

FAQ about Marianne, France’s cultural symbol

Who is Marianne in France?

Marianne is the cultural symbol of the French Republic. She represents liberty, citizenship and shared civic values rather than a real person, and has been used since the French Revolution to embody French national identity.

Is Marianne a real historical figure?

No, Marianne is not a real person. She is an allegorical figure created to symbolize republican ideals and to give a human, cultural face to abstract political values.

Why is Marianne important in French culture?

Marianne is important because she visually expresses France’s core values of liberty and civic responsibility. Her presence in public spaces reinforces a shared cultural identity beyond politics.

Where can you see Marianne in France?

Marianne can be seen in town halls, on official stamps, coins, monuments and artworks. She is one of the most recognizable cultural symbols in everyday French public life.

Why does Marianne often wear a Phrygian cap?

The Phrygian cap is a historical symbol of freedom. Marianne wears it to represent liberation from oppression and the revolutionary roots of French civic culture.