Who was Stanislas Leszczynski? Stanislas Leszczynski (1677-1766) was a king of Poland who became the last Duke of Lorraine. Father-in-law of the French king Louis XV, he made his mark on history as a humanist and builder. He was responsible for the creation of the famous Place Stanislas in Nancy (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and the cultural development of Lorraine before it was definitively annexed by France.

I / Stanislas Leszczynski: King of Poland at age 26

The city of LVIV today. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: Ruslan-Lytvyn via depositphotos.

A cultured and athletic young Polish nobleman

Stanislas was born on October 20, 1677, in Lviv, now in Ukraine, but at the time part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, or Poland. Poland was much larger then than it is today, encompassing not only present-day Poland, but also the Baltic States and Ukraine. The Leszczynski family originated in Bohemia. They settled in Posnania in the 9th century. Stanislas's father, Raphael, was the "staroste," or governor. A noble family, certainly, but far from being one of the great families that shared Poland. In 1696, Stanislas emerged from anonymity by delivering the eulogy for King John Sobieski. He was talented, spoke well, and impressed the people who had come to attend the funeral. Two years later, in 1698, he married Catherine OPALINSKA, who brought him a dowry of several hundred towns and villages (that's how the Polish nobility counted at the time). They had two daughters: Anne, born in 1700, and Marie, born in 1703.

Portrait of Stanislas around 1700 (anonymous painter). Source Monsieurdefrance.com: webart.nationalmuseum.se, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3250854

He therefore enjoyed a good position. He was curious and cultured. For example, he had made his "tour of Europe," visiting the major European cities. This was common among English nobles, but rarer in Poland. We know that he stayed in Paris for a while and discovered the city, without knowing that he would return 40 years later to see his daughter. He was also a friendly guy. It's hard to imagine when you see his statue and the big, jolly man who sits enthroned in the middle of the square that bears his name in Nancy, but in 1700, the moment when his destiny changed, he was a dashing, very athletic boy with a hearty appetite (like his mother Anna JABLONOWSKA, a great food lover before the Lord), but he drank little, which made him something of an oddity among the Polish nobility. Sober (well, almost), athletic, and cultured, these three qualities caught the eye of an extraordinary man. And that's what changed his life...

The alliance with Charles XII of Sweden, known as "Ironhead"

King Charles XII (1682-1718) attributed to David von Krafft/Johan David Schwartz — www.nationalmuseum.se, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=482449 / Illustration chosen by monsieurdefrance.com: www.nationalmuseum.se, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=482449

In 1699, Sweden was ruled by a child. The king was 17 years old, his name was Charles XII (1682-1718), and he had been king for two years when his neighbors decided to take advantage of his inexperience to attack Sweden and grab large chunks of its territory to expand their own possessions. Russia, Denmark, and Poland formed an alliance and attacked Sweden, thinking they would make short work of it. They were sorely mistaken. Charles XII was a military genius. Highly educated (he spoke several languages) and extremely seasoned (he was athletic and slept in the snow), he was passionate about war (to the point of renaming the queens in chess as generals). And this young man not only resisted, but also swept through his opponents before launching an assault on impenetrable Russia. Highly talented, Charles XII defeated his opponents one after another. He first attacked Denmark and laid siege to Copenhagen. A treaty was signed. Next, he attacked the Russians. The Battle of Narva (November 30, 1700) was a huge victory, as the Swedes, fighting at a ratio of less than 1 to 4, crushed the Russians and killed 15,000 of them, while suffering only 667 casualties on the Swedish side. With his hands free and determined to press his advantage in Russia, Charles XII, 18 years old and nicknamed "Iron Head" for his stubbornness, attacked Poland, which he had already defeated once in Riga.

The Battle of Narva by Alexander von Kotzebue / Illustration selected by monsieurdefrance.com commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4111346

For Poland, it was King Augustus II who decided to join Denmark and Russia in their assault on Sweden. It was a bad move on his part. The Polish armies were routed by Charles XII's troops, who literally pushed them before them. Augustus II, who was also King of Saxony, was forced to flee and take refuge in his Saxon kingdom, while Charles XII reached Warsaw, the capital, which he was preparing to conquer. The Poles sent a delegation to negotiate. This delegation, led by the Cardinal Primate of Poland, included the young Stanislaus. And Charles XII liked Stanislaus. They were almost the same age, both athletic and cultured. At the end of the negotiations, Charles XII's conditions were clear. Augustus II must renounce the Polish crown, there must be a new election, and as Charles said of the young Stanislas, "he will always be my friend," everyone understood that Stanislas would have to be elected King of Poland. There was no choice! Augustus II, who had taken refuge in Saxony, signed the treaty. Stanislas I was elected King of Poland on July 12, 1704. He was 27 years old.

The coronation of Stanislas in July 1704 / Illustration selected by monsieurdefrance.com: National Library of France, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org

The Kingdom of the Two Nations: How the elective monarchy worked

The election of the King of Poland is unique. Upon the death of the reigning king, the Polish nobles gather in the vast Wola plain on the outskirts of Warsaw and elect their king. His powers are very limited, but he controls the treasury and can appoint people to important positions. He is rarely Polish, often a foreigner. Thus, the king who preceded Stanislas (and who would soon take his place) was King of Saxony under the name Frederick Augustus I and, at the same time, King of Poland under the name Augustus II. Interestingly, some Frenchmen have been kings of Poland. Henry III (1551-1589) was elected king of Poland on May 11, 1573, thanks to his mother Catherine de Medici, who wanted a throne for her favorite son, the younger brother of the king of France. He reigned for two years and one day before secretly fleeing back to France to take the throne left vacant by the death of his brother Charles IX. Similarly, the Prince of Conti was elected in 1697, but he dragged his feet and even refused to disembark when he heard the cannons of his rival (already Augustus II) welcoming him to Danzig (now Gdansk).

The election of Stanislas' rival, Augustus II, on the Wola plain near Warsaw in 1697. Illustration chosen by monsieurdefrance.com: painting by Jean-Pierre Norblin de La Gourdaine — www.wawel.krakow.pl, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5045474

An election, then. And not like we imagine today. A vast field with 40,000 people on it. A huge camp where you come across princely dynasties who arrive with their soldiers, servants, and women who entertain these men for money, but also minor nobles who have nothing but their horses. People drank, talked, and argued. It was even quite risky. Votes could be bought and the person who paid the voters the most won. As for Stanislas, it was Charles XII who imposed the result, but many nobles remained loyal to Augustus II. Others considered that, even with all his qualities, Stanislas had been elected through outside interference. His throne was very fragile. It only held because Charles XII was victorious. Unfortunately for him, the tide was about to turn. Charles XII decided to press his advantage and attack Russia. He got a little carried away, and it would cost him dearly...

The fall of Charles XII and the end of Stanislas's first reign

La bataille de Poltava et la défaite de Charles XII de Suède / Par Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada — Detail of Diorama of Battle of Poltava - Battle of Poltava History Museum - Poltava - Ukraine - 03, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org

In 1709, Charles XII set out to conquer Russia. And like the two who would attempt it after him (Napoleon I and Hitler), he failed. Because Russia is absolutely immense and the climate is extreme for much of the year. At the head of 45,000 men, he advanced into the Russian Empire with the intention of taking Moscow, which was still the largest city in Russia, even though Peter I had begun construction of a new capital, St. Petersburg, a few years earlier. The Russians employed a scorched earth strategy, destroying villages and crops in advance that lay in the path of the Swedish army, which quickly ran out of everything, especially food. And 1709 was the year of the "great winter" in France and Europe. It was the worst winter ever recorded, and remains unmatched to this day. In Versailles, wine froze in glasses. In the countryside, trees cracked in the frost. People could walk across the port of Marseille. Birds literally fell from the sky. Needless to say, in Russia, it was appalling. The winter and the lack of food decimated the Swedish army when it arrived in front of Poltava in July 1709 to besiege the city. The battle raged, but the Swedes were no match for the Russians, who defeated them soundly. Charles XII was forced to flee to Turkey, in the Ottoman Empire, an old enemy of the Russian Empire. He hoped to persuade "the Sublime Porte" (the Turkish government) to help him. In other words, Stanislas's throne is in a very precarious position. He owes it to Charles XII, and it held out as long as the King of Sweden was victorious. With Charles XII defeated, Augustus II, Stanislas's rival, sets out to reconquer his lost throne. Stanislas had to flee from the Saxon armies. He fled so quickly that he even left his youngest daughter, little Marie, behind in a manger. He would have to return very quickly to fetch her. Defeated and eager to salvage what he could, Stanislas wrote to Charles XII to negotiate and offer to return his crown to Augustus II in exchange for recovering his family's lands. Charles XII flatly refuses and makes it clear to Stanislas that, if he made him king, he can also make someone else king. Stanislas decides to go to Turkey to meet with Charles XII to persuade him of the merits of his idea to return the Polish crown...

Stanislas' escape: The king disguised as a simple officer

Since the Russians are against his protector, Stanislas cannot travel safely to Turkey via Russia. Similarly, he prefers to be discreet with regard to the Turks. He therefore decides to disguise himself... In French. This is quite ironic when we consider that 30 years later, his contemporaries would remark on Stanislas's strong Polish accent when he spoke French. But anyway, disguised as a French officer, he manages to cross several borders until a Turkish official does not believe him. "I am a major," Stanislas tells him in Latin. "Majorum Est," replied the Turk, which means "you are much higher than that." An amusing play on words, but one that does not change the reality: Stanislas was not welcomed but rather taken prisoner by the Turks, who took him to Bender, in Moldova, to join Charles XII, who was imprisoned there in a house. He was imprisoned because he had tried to escape several times, even attacking the Turks who surrounded him (he got his spurs caught in his cape and fell, which allowed them to arrest him). With Charles XII and Stanislas both prisoners, Augustus II of Poland regained the crown he had lost.

The fortress of Bendery, in Transnistria/Moldova. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: Byelikova via depositphotos.

In Bender, Stanislas discovers Ottoman culture. He enjoys walking around and exploring the architecture before his prison conditions become harsher a few months later. It is also there that he discovers the "chibouque," a long pipe, which he learns to smoke (and which will cause his death 50 years later, but we are not there yet).

Exile to the Duchy of Zweibrücken

While his enemies were now besieging Sweden on its own soil, Charles XII negotiated his release with the Turks and left in 1714 to defend his kingdom. While waiting to reconquer Poland, the Swedish king offered Stanislas the Duchy of Deux-Ponts, in present-day Germany, which belonged to Sweden in the 18th century. Stanislas settled there immediately and was reunited with his wife and two daughters, whom he had not seen for several years. He read extensively and embarked on a building project, which would become one of his great passions. He had the "tchiflik" built, inspired by the Turkish tchifliks, which were large agricultural estates. In Zweibrucken, Stanislas's tchiflik was a small castle consisting of several separate buildings and terraced gardens. He was very popular with his new subjects. It must be said that he was a really nice guy. So much so that one of the mercenaries sent by his rival, Augustus II, to kidnap him and put him in prison, spilled the beans and denounced the plot to Stanislas, saying that it was strange that anyone would want to harm such a likable man. The people of Lorraine would also recognize this a little over 20 years later.

Zweibrucken a few years after Stanislas's visit. 19th-century engraving / Via wiki commons / Wikipedia.

It was here that Stanislas suffered the pain of losing his eldest daughter, Anne Leszczynska (1699-1717). She died at the age of 18, a victim of pneumonia and, sadly, of the numerous doctors called to her bedside by her father, who killed more often than they saved. She was buried in Gräffinthal Abbey, leaving her parents inconsolable. Stanislas even made Marie, his youngest daughter, swear never to mention Anne's name in his presence. She kept her promise so well that Louis XV, her husband, only learned very late in life that she had had an older sister. This tragedy brought Stanislas and his daughter Marie much closer together. Their almost symbiotic relationship became legendary.

Anne Leszczynska (1699-1718) Par Johan Starbus / Source de Monsieurdefrance.com : webart.nationalmuseum.se, Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14954433

A few months later, in 1718, Charles XII died. A bullet pierced his head, tearing a hole in his hat, as he stepped forward to inspect his attack lines from a ditch. There is great mystery surrounding his death because it is not known which side the bullet came from. Officially, it came from the Russian side. Unofficially, many historians wonder whether the bullet came from Charles XII's own camp, fired by Swedes who were fed up with the war and Charles XII's character. It must be said that a few years earlier, when the Swedish Diet, the Parliament, had asked the king to return to the country, Charles XII had sent one of his boots to preside over the Diet. With Charles XII dead, his heirs made peace and hastened to save what could still be saved. And they kicked Stanislas out of his little duchy of Deux-Ponts. There he was, homeless and ruined. So ruined that he was forced to pawn his wife's jewelry to a moneylender in Lunéville, Lorraine, while traveling to Alsace. Upon learning of this, the Duke of Lorraine, Leopold I, bought the jewelry back from the moneylender and returned it to Stanislas. The two men did not know that they would live in the same castle at two different times. Calling on France for help, Stanislas received a reply from the Regent Philippe d'Orléans (1674-1723) stating that "France has always been a refuge for unfortunate kings." He was given a small pension and lodged in Alsace, in a bourgeois house in Wissembourg. It seemed that Stanislas, who was now 40 years old, would spend the rest of his life reading and hunting, listening to his wife Catherine telling him all day long that he was a loser. However, he was the victim of an assassination attempt by his rival Augustus II, who had his chibouque, a long pipe, poisoned. It didn't work (the Americans would try the same trick with Fidel Castro's cigars two centuries later, and it wouldn't work either). A dreary life, then. But... Once again, a king would turn his life upside down, and especially that of his daughter, Mary.

II / How Stanislas became Louis XV's father-in-law

Marie Lezckzinska one year after her marriage to King Louis XV of France. Illustration chosen by monsieurdefrance: painting by Alexis Simon Belle — www.zamek-krolewski.pl, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=424431

Louis XV: A young King of France in search of a wife

In 1715, on the eve of his death, Louis XIV (1638-1715) had only one descendant left and France was struggling to recover from the War of Spanish Succession. In 1700, this war was launched against France by many European countries when Louis XIV decided to support the rights of his grandson, Philippe d'Anjou (1683-1746), to the Spanish throne. A Bourbon on the Spanish throne was intolerable to many powers that did not accept that the Bourbon dynasty could hold the thrones of France and Spain. Moreover, Louis XIV's grandson could claim both crowns if his older brother died. In 1713, after a major conflict, a compromise was reached. Philip of Anjou could keep the Spanish throne on the express condition that he renounce the French throne if it came to him. And this was not impossible. Disease (smallpox, measles, etc.) and accidents (a fall from a horse) decimated the other descendants of Louis XIV to such an extent that by 1715, the king had only one heir left. A 5-year-old boy: Louis, Duke of Anjou, the future Louis XV. The boy, who was only the youngest son, was not treated by doctors when he contracted measles, unlike his older brother. And at the time, doctors killed more often than they cured. It was thanks to Madame de Ventadour, the child's nurse, who closed all the doors, that Louis XV was saved... by not being treated. He was alive, of course, but death was common among children in the 18th century. If the child, Louis XIV's only direct heir in France, also died, there would be war because the King of Spain could legitimately claim the French crown, even though he had renounced it in writing, because the fundamental laws of the kingdom prohibited renouncing the crown, and because he would not allow the Orléans family, descended from Philippe d'Orléans, brother of Louis XIV, to take the throne. To avoid this, the young king must be in good health and, above all, have children. It was therefore decided to marry him off.

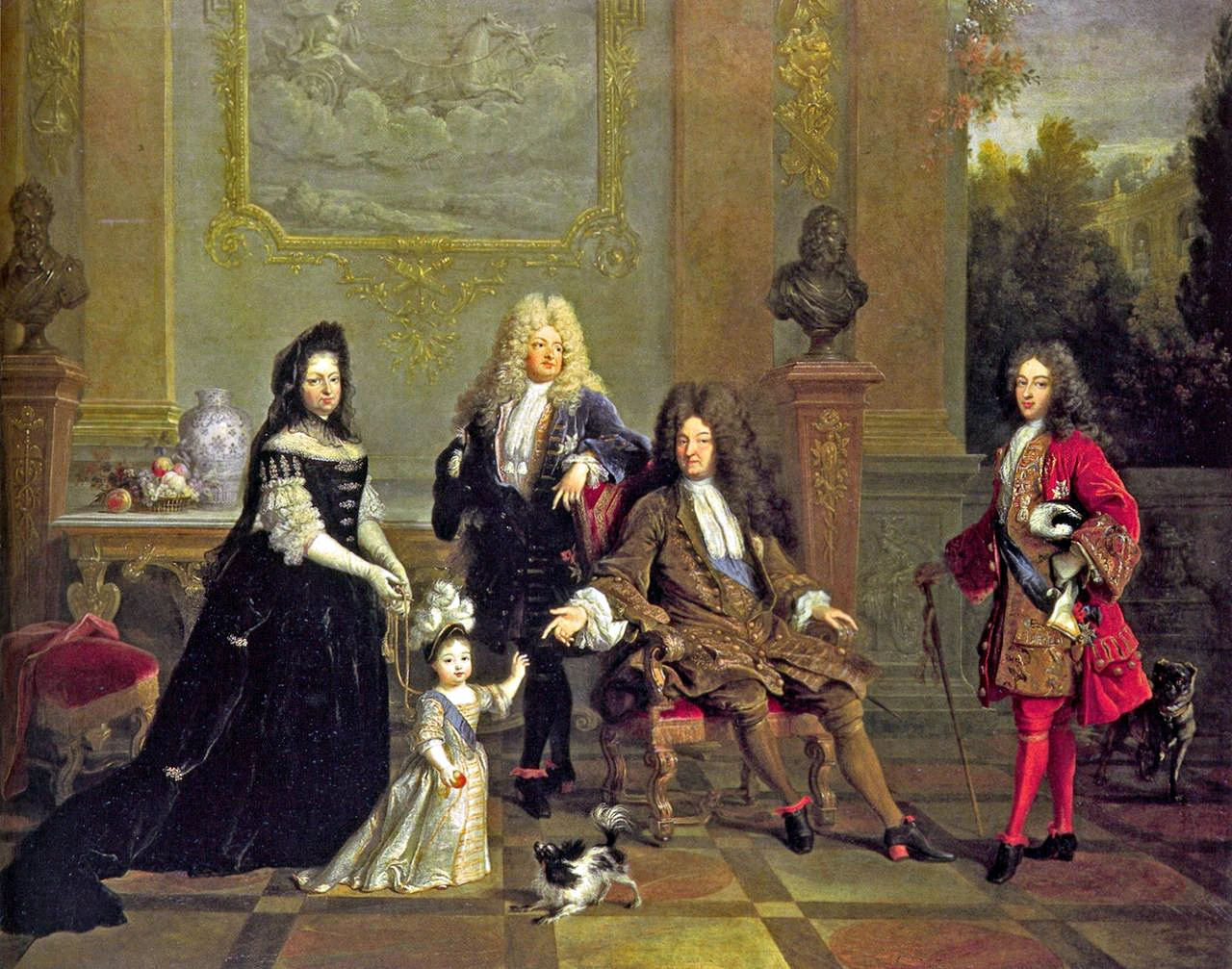

Louis XIV poses in 1710 with his son, the Dauphin (standing and blond), his grandson, the Duke of Burgundy, and his great-grandson, the Duke of Brittany, elder brother of the future Louis XV. None of them would outlive the king. They all died within the next five years. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=153698

The unexpected marriage between Marie Leszczynska and Louis XV

At first, however, politics took precedence. The regent, Philippe d'Orléans, decided to betroth the young Louis XV to Marie-Anne-Victoire of Spain (1718-1781). The king was 11 years old, and the future queen was only 3. Needless to say, children were not on the horizon. Louis XV wept profusely upon hearing the news. He did not speak to his future wife when she arrived in Paris, entrusted to the French court by the Spanish court to be raised there until she was ready to actually marry the young king. The young future queen was led to believe that the king's silence was a sign of affection and that he did not speak when he loved someone. One day, to a courtier whom the king did not look at because he was in disgrace, the young child said, "The king loves you very much, he has not spoken to you at all." Why a marriage with such a large age gap and at least 12 years of waiting to have an heir? Politics! The Regent managed to marry off one of his daughters, who went on to marry the future King of Spain in exchange for the King's marriage. Everything changed with the Regent's death in 1723 after one of his famous fine dinners.

Louis XV in 1721 (1710-1774) was the only French descendant of Louis XIV. He had to marry and have children, otherwise France would become Spanish. Source: Monsieurdefrance.com: Wikipedia.

Indigestion due to marriage

In 1723, the Duke of Bourbon became the de facto prime minister of the young King Louis XV. He was the grandson of Louis XIV on his mother's side (his mother was one of the king's daughters with his mistress, the Marquise de Montespan) and of the Grand Condé on his father's side. Ugly, lame, and one-eyed, he was nevertheless the object of all the care of his mistress, the Marquise de Prie, who sought a wife for him. A woman who would be discreet and who, being of humble origins, would have no choice but to accept that Madame de Prie would not only be present in the prince's life but would also run his household. Her choice fell on Marie, the daughter of Stanislas. The daughter of a king, even if he is an elected king, is still a king, and a very poor one at that, since she lives in a bourgeois house in Alsace on the subsidies that France is willing to grant her father in exile. Talks begin with Stanislas. Except that the marriage will not take place. Indeed, the young king's health is a cause for concern.

Louis XV in 1723, two years before his marriage. Painting by Jean-Baptiste van Loo / Image selected by monsieurdefrance.com: GAH85hB-TeU40w — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13397810

Indeed, Louis XV, aged 13, was very athletic. He spent hours hunting on horseback. And at the time, sport was considered very bad for your health. Pierre CHIRAC (1657-1732) was not far from thinking that such an athletic lifestyle could kill the king. And if the king died before having children, war could break out. When it came to his diet, what ultimately decided the Duke of Bourbon's fate was indigestion. Blessed with the excellent appetite typical of the Bourbons (Louis XIV had the appetite of a giant), Louis XV fell ill in 1725. Indigestion that confined him to bed and worried the doctors. The Duke of Bourbon was seen wandering the corridors of Versailles, very concerned for the king and therefore for his position as minister. "It's decided, I won't be caught out again!" he is said to have remarked. What is certain is that, even after the king had recovered and returned to hunting, the Duke of Bourbon decided to change everything. He canceled the king's engagement to the young Infanta of Spain, who was sent home. Much loved because she was very kind, she was simply told that her parents wanted to see her again, and the 7-year-old girl set off for Madrid. She would eventually marry a king of Portugal. France came close to war with Spain, which broke off all diplomatic relations (it would be forced to back down, as it had no allies). And the search began for a wife for the king.

Marie Leszczynska: A Queen to ensure the continuation of the French royal line

The Marquise de Prie is said to have been behind the proposal to make Marie the wife of Louis XV. Image chosen by monsieurdefrance: based on Carl Van LOO via wikicommons / wikipedia.

What is certain is that the future queen must be able to have children immediately. So a list is drawn up. There are 98 of them, and it is said that Madame de Prie had Marie Lezscksinska added at the last minute. So there are 99 princesses who could marry Louis XV. In front of the young king, the list of candidates is reviewed and a process of elimination begins. Those who are not Catholic or whose conversion to Catholicism would be complicated are eliminated. French women are eliminated, because raising a French family would be too much of an upheaval. Those with whom relations are strained are eliminated. And the choice began to get complicated. And they began to see Marie in a new light. After all, even if her family was of minor nobility compared to the King of France and all the great families of Versailles, even if her father was dethroned and poor, and even if he had been elected, which made his title less powerful at a time when everything depended on birth, Marie is still the daughter of a king. And since her father does not reign, France is not at risk of being dragged into a war in the event that the queen's country of origin, and therefore an ally of France, enters into conflict, as was often the case in the 18th century. If he were to regain his throne, which is always possible, France would regain a long-standing ally: Poland, which poses an excellent threat to the rear of its hereditary enemy, the Habsburg family, which rules Austria and the Holy Roman Empire. Admittedly, Marie was 25 years old, which was the age limit for marriage at the time, and she was considered almost old. She was in excellent health, riding horses with her father, good-looking (we discreetly checked), cultured (but no one at Versailles cared about that). She was available because Stanislas had refused to allow her to marry a certain Marquis de Courtanvaux, whom he did not consider high-ranking enough for her and for whom he demanded a ducal title in order to consider a marriage (which was therefore impossible). the Duke of Bourbon could have married her, but he prefers to deal with the most urgent matter: the king is soon to be a father, and she can have children right away. The decision is finally made. A messenger is sent to Alsace.

"My daughter, you are Queen of France": The announcement of destiny

The historic center of Wissembourg in Alsace, where Stanislas was living when he learned of his daughter's marriage to Louis XV. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: DaLiu via depositphotos.

It was during a hunt, while riding in a carriage through the Alsatian countryside, that Stanislas saw a messenger on horseback approaching, who handed him two letters, one from the Duke of Bourbon and the other from the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Stanislas realized that his daughter's marriage to the Duke of Bourbon, which had been in the works for several months, was about to take place. He opened the Duke's letter first, read it, stood up, and then fainted in the carriage. Revived a few moments later, he rushes home, climbs the stairs four at a time, and opens the door to his daughter's room. In the room, Marie and her mother, Catherine, are doing needlework. The king then exclaims, "My daughter! Let us fall to our knees and thank God!" Marie then said to him, "Father? Have you been called back to the throne of Poland?" Stanislas replied, "No, my daughter, Heaven has granted us something even better: you are Queen of France!"

The "Marriage of Cinderella" that stunned Europe

The marriage of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska as seen in a period engraving. Source from Monsieurdefrance.com: Gallica.fr / BNF

This marriage is truly a fairy tale. Just think about it: one is a king and rich, the other is a princess and poor. Louis XV ruled over the largest country in Europe. It was by far the most populous, with 25,000,000 inhabitants, while Great Britain had barely 10,000,000. France was the arbiter of Europe. Versailles was the envy of monarchies. Paris was already the City of Light. Marie, on the other hand, has almost nothing. She doesn't even have a pair of shoes fit for her reception in Strasbourg by Cardinal de Rohan in preparation for her wedding. Everything has to be bought for her. Jewelry is sent to her from Versailles. On site, dresses and her trousseau are made. In Paris, the news causes a stir and the French are angry. Marie does not seem worthy of a king of France, let alone this young 15-year-old king adored by Paris. She is considered too poor. Her father is not considered king enough. Libels are written. Criticisms were made. Some even claimed that Marie had webbed feet. The attacks on her physical appearance and health were so numerous that Versailles discreetly sent doctors to check on the health and figure of the future queen. Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchess of Lorraine and niece of Louis XIV, summed up the opinion of the Court of Versailles when she wrote: "I admit that for the King, whose blood remained the only pure blood in France, it is surprising that he should be made to enter into such a misalliance and marry a simple Polish lady, for [...] she is no more than that, and her father was king for only twenty-four hours."

Marie in 1726, one year after her marriage. Queen of France. Image selected by Monsieurdefrance.com: Painting by François Stiémart/ After Jean-Baptiste van Loo/ Formerly attributed to Pierre Gobert/ Maurice-Quentin de La Tour Palace of Versailles. http://forum.alexanderpalace.org/, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11861590

Méré, sent by Versailles, reassures the court by writing, "She has a beautiful, colorful complexion, fresh water and sometimes snow water being all she needs for makeup [...]. In winter, she rises between 8 and 9 o'clock, dresses, and then goes to the apartment of the queen, her mother. She attends mass with the whole family. She speaks German, French very well, without an accent [...] she has a flexible mind, which will take on whatever form and shape one wishes." This is a fairly accurate portrait. Marie is cultured, intelligent, devout, and so kind that she will win the hearts of the French to the point of becoming the archetype of the Queen of France; discreet, elegant, and generous. It is to her that the first ladies of France of our time owe their role as fashion icons of their era and leaders of charitable organizations.

The chapel at the Palace of Fontainebleau where Louis XV and Marie Lezckzinska were married in 1725. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: isogood via depositphotos.

The first ceremony took place in Strasbourg Cathedral, packed with people, on August 15, 1725, the day of the Assumption and the day chosen by Mary. The queen then left for Fontainebleau where the ceremony would take place in the presence of the king. The journey was grueling for the huge caravan of carriages and carts carrying the queen and her furniture across eastern France. It rained cats and dogs, to the point that the queen's carriage fell into a ditch and she had to be pulled out by her arms. The ladies-in-waiting move the silverware from a wagon to take its place so that they can keep their feet dry and enjoy the comfort of straw rather than the waterlogged carriages. Everyone is sulking, except Marie, who has seen much worse in Poland when she fled from the armies of her father's rival.

Louis XV in his coronation robes in 1730. He is 20 years old. Image selected by monsieurdeFrance.com: painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud — Source unknown, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1751541

The Queen arrives at Fontainebleau as the rain stops falling. A carpet is laid out in front of her so that she can walk without getting wet. The King approaches. She is about to kneel, but he stops her. He is happy. So is she. The wedding is celebrated the next day. It takes several hours of preparation to perfect the Queen's extremely heavy dress, which she nevertheless wears without complaint. Louis XV, impatient, speeds things up. The bedding ceremony takes place. It is a beautiful wedding and, as the Duke of Bourbon writes to Stanislas a few days later, it is consummated, since the young Louis XV "gave the queen seven proofs of tenderness during the night." Their marriage would be prolific, as Louis XV and Marie Leszczynska would have 10 children, including twins. Seven of them would reach adulthood.

Mission accomplished. After several daughters, Marie gave birth to the Dauphin in 1729. Image selected by Monsieurdefrance.com. Painting by Alexis Simon Belle — http://www.photo.rmn.fr/LowRes2/TR1/V3I0G/89-000310-02.jpg, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=424438

Stanislas's stay at the Château de Chambord

For Stanislas, it was decided that the father-in-law of the King of France could not remain in his Alsatian home and that he should be offered the Château de Chambord. The immense castle of François I with its 365 windows. It was a poisoned gift, however, as the marshes surrounding the royal residence were breeding grounds for mosquitoes and malaria was ravaging the Sologne region. Several members of Stanislas's court in exile were affected by the disease and some died. Stanislas was 48 years old. He resumed his daily routine, coming to Versailles once a year to congratulate his daughter on her childbirths. He read and wrote. His wife grumbled. His mother, Anna, mechanically gave herself indigestion. They keep themselves busy as best they can. But once again, fate catches up with Stanislas. Poland is back in the news. Why? Because Augustus II, his lifelong rival and enemy, has died. The Polish crown is once again up for grabs...

III / Stanislas, Duke of Lorraine and Bar: Success at 60

Stanislas at the age of 63. Engraving. Source from Monsieurdefrance.com: Limedia.fr https://galeries.limedia.fr/ark:/31124/dc1207mj4l7z7g81/

The attempt to regain the Polish throne

Who said that life was over after 60? Not Stanislas, who set out to tempt fate once again in 1733. His goal was to regain the throne he had lost 24 years earlier. It must be said that his rival had "finally" died. With Augustus II dead, the throne was available, even though Augustus's son intended to become king of Poland himself and the Russians had their own candidate. France supported Stanislas in his claims. It must be said that France had never really recovered from having the daughter of a king without a crown as its queen. It is a very risky gamble for Stanislas, who is literally risking his life, as the Russians or Poles loyal to the King of Saxony will not miss their chance if he is caught. And prison would be the mildest possible outcome in that case. It is this danger that explains the tears of his daughter Marie when he comes to say goodbye to her for the last time at the court of Versailles in July 1733. He is welcomed with great pomp and ceremony and it is still in grand style that he travels to Brest to board a ship bound for Poland. A very public departure, then. And that was the intention...

The art of camouflage: A new disguise for Stanislas

The port of Brest in the 18th centuryBy Louis-Nicolas Van Blarenberghe. Image selected by monsieurdefrance.com via Wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons.

On the ship bound for Brest, he is called "the frock coat" because he is rarely seen and only from a distance. A slightly overweight man, he only comes out on the rear crow's nest to walk around and then immediately returns to his cabin. The small contingent of soldiers who embarked with Stanislas ended up nicknaming King Stanislas "the frock coat" because they could only see his outfit from a distance. The ship sails slowly, wary of English boats, which are always capable of boarding it, as the English have (already) decided that they alone can decide who can sail the seas and who cannot. The ship continued on its way to Poland while, by land, which was much faster, a small carriage transported a merchant and his valet as quickly as possible. The valet was a little heavy, spoke little when spoken to, and arrived in Warsaw in just a few weeks. It is in fact this small, discreet carriage that is transporting Stanislas, the real one... The ruse allowed him to reach Poland much more quickly, while a lookalike, the Chevalier de TIHANGE, took his place in the spotlight to make people believe he had left by boat. The real Stanislas, meanwhile, left in the opposite direction, disguised as a valet of the Count of Andlau, a loyal supporter of his daughter. And so it was safe and sound, and happy to have pulled off quite a surprise, that Stanislas made his entrance into Warsaw, where the Polish nobles had gathered to elect the king. The 50,000 electors proclaimed him king four days after his arrival, on September 12, 1733. He received the keys to the city and took possession of the Royal Palace before attending a thanksgiving mass at the cathedral. Stanislas's second reign began. It would last... 10 days.

The heroic siege of Danzig (Gdańsk)

The city of Danzig, now known as Gdańsk in Poland. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: Patryk_Kosmider via depositphotos.

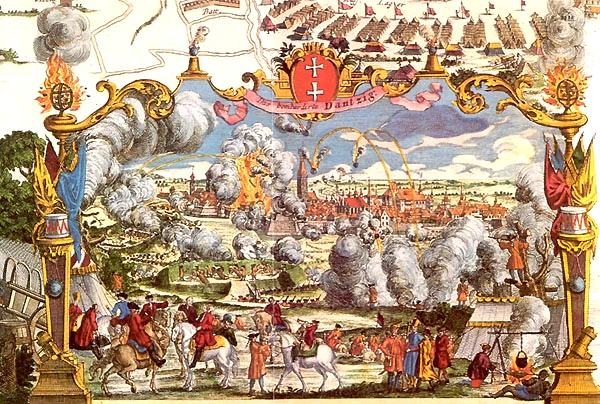

The Prussians, Russians, and Austrians were determined to impose their candidate, namely the son of Augustus II, Frederick Augustus of Saxony (1696-1763). Much closer and more motivated than the French, the Russians lined up 20,000 men who arrived in Warsaw and imposed the election of Frederick Augustus, who became Augustus III of Poland in January 1734.

Augustus III, King of Poland, ultimately prevailed over Stanislas. Interestingly, his daughter married Stanislas' grandson, the Dauphin of France, and it was from this marriage that Louis XVI, Louis XVIII, and Charles X, kings of France, were born. Portrait chosen by Monsieurdefrance.com: By Raphael Mengs — www.kunstkopie.de, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7303625

Stanislas, meanwhile, was forced to flee and took refuge in Danzig, which was immediately besieged by the Russians. The city was bombarded but held out (much to the surprise of Stanislas, who was an aristocrat after all and convinced that mere merchants would lack courage, as if courage were reserved for nobles... ). France declared war on Austria in the name of the insult to the king's father-in-law and attacked Austria, as always, through the Austrian Netherlands (today's Belgium). Other troops set out through the Holy Roman Empire and Italy. In Versailles, Cardinal de Fleury, Louis XV's prime minister, had no intention of helping Stanislas any more than that. However, he was persuaded and sent a squadron of three ships and a few hundred men to support the King of Poland. The squadron passed through Copenhagen, where it was received by the Count of Plélo, the French ambassador to Denmark. So few men and so little French honor enraged him terribly.

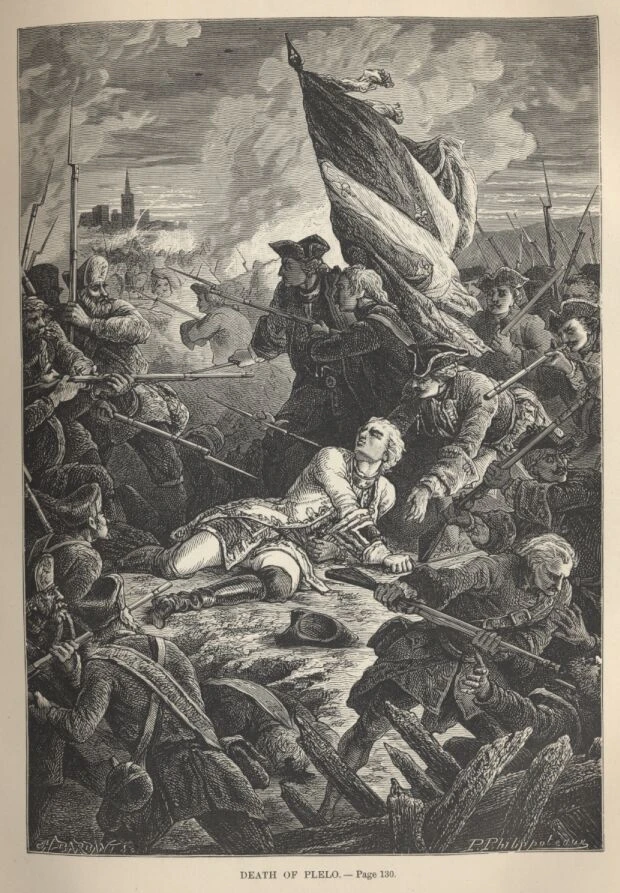

The death of the Count of Plélo in 1734 as seen by Paul Philippoteaux in the 19th century. Source from Monsieurdefrance.com: Wikicommons / Wikipedia.

Louis de Bréhan, Count of Plélo (1699-1734) was the French ambassador to Denmark. A great intellectual, he was passionate about literature (the Bibliothèque Nationale de France owes most of its collections of works from the North to him) and science (he conducted chemical experiments with his wife and even nearly died several times due to explosions). He was also the grandnephew of Madame de Sévigné, whose sharp wit he shared. And this man was stunned to see how little regard Versailles had for Stanislas. He considered the small military convoy sent to help Danzig withstand the Russian siege to be dishonorable. He struggles to find more weapons and ammunition and, contrary to his orders, he even engages with the military, forcing them to return to Danzig when, judging the battle to be lost in advance and not having orders from Versailles to intervene, they were planning to leave for Brest. Plélo took matters into his own hands and brought everyone back to Danzig. He even led the assault on the Russian troops from the front line. This cost him his life. His body was returned to the French a few hours after the battle, riddled with bayonet wounds. He fought for nothing, as he was sure of losing the battle and even of dying, but he died for the honor of France. Empress Anne I of Russia was not mistaken. She hung the count's portrait in her bedroom. He was the first French officer in history to fall under Russian fire. In France, his widow, Louise, whom he nicknamed "the cat," died of grief a few years later (they were very much in love), leaving behind an orphan.

Stanislas' incredible escape through the marshes

For Stanislas, the situation is dire. Taking refuge in the French embassy, out of reach of Russian cannons, he knows that if he is caught, he will die, as the Russians have put a price on his head. He must therefore flee. It is impossible by sea. It is impossible to make a military sortie. So they choose... Disguise. Stanislas has already done this twice in his life, and this time will be the last. They disguise the king as a small shopkeeper and he leaves the embassy on the sly before retracing his steps. He needs worn boots, his own are too new, he will be spotted. So we steal boots from a completely drunk French soldier and the king leaves the city. It will take him several days to get out of the inextricable network of marshy paths that surround Danzig at the time. Nearly caught several times (he finds himself perched at the top of a barn while Russian soldiers search below), recognized but never denounced by the Poles, he manages, at the risk of his life, to reach the lands of the King of Prussia, in the back of a cart, on June 27, 1734.

Engraving of the Siege of Danzig / Image selected by monsieurdefrance.com: By anonymous plate — http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje43/text12p.htm, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2454454

In Paris, people are laughing. In the streets, we read libels such as this one: "Is he king, or is he not, this prince we mourn? Is he fleeing? Is he going into battle? We do not know. Where is poor Stanislas? Will we ever see him again?" In Versailles, Marie and her mother, Catherine, are so overcome with anxiety that a fake gazette is produced for the Queen. This gazette contains only false, reassuring news so that she, who is pregnant, will not worry. In Koenigsberg, King Frederick William first tries to sell Stanislas to the Russians in exchange for some land, before changing his mind and treating him as royally as possible to please France, with whom he is reconciling. It must be said that the two men get along well. They have a good appetite and, between two jugs of beer, they talk. Frederick Augustus had an idea for Stanislas: Poland was a lost cause. So why not Lorraine?

A marriage of love.

Duke François Etienne of Lorraine and Bar and his wife Marie-Thérèse of Austria in 1747. Photograph selected by monsieurdefrance.com: Franz Karl Palko — Personal photograph in the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum von Pappenheim, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17734702

Let's leave Poland for a moment and head to Austria. In 1734, the Duke of Lorraine was living in Vienna. Francis III Stephen, Duke of Lorraine and Bar (1708-1765), was born at Lunéville Castle. He was the ninth and one of the few surviving children of Duke Leopold I the Great (1679-1729) and Duchess Elisabeth-Charlotte d'Orléans (1676-1744), daughter of "Monsieur," Philippe d'Orléans, brother of Louis XIV. Leopold literally rebuilt his duchies of Lorraine and Bar, which had been severely damaged by the Thirty Years' War and occupied by France for nearly 60 years. He recovered them through the Peace of Ryswick in 1697 and even had to repopulate them, as the war and the plague had taken such a heavy toll (it is said that one in two Lorrainers died in the 17th century). Leopold, who turned his duchy into a flourishing state, resumed the policy that had allowed Lorraine to remain independent: a marriage on the left, a marriage on the right, in other words, a marriage on the French side and a marriage on the German side. Having married a Frenchwoman, he placed his son in Vienna with his cousin, the Emperor of Austria, so that he could receive the education befitting a sovereign prince. And love did its work. Maria Theresa (1717-1780), daughter of the Emperor, fell in love with the young Francis of Lorraine. And they wanted to marry in 1734, when Francis became Duke of Lorraine and Bar upon his father's death in 1729. This marriage was impossible because France would not tolerate Lorraine becoming Austrian through the marriage of its duke, which would make it an Austrian stronghold in the heart of France. The situation, which had been deadlocked until then, could well be resolved by Stanislas's setbacks in Poland. And why not end this war with a marriage rather than a life annuity?

The imperial couple and their children. They are the parents of Marie Antoinette, who would marry Louis XVI, Stanislas's great-grandson. Painting selected by monsieurdefrance.Com Martin van Meytens — [1], Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1619608

1737: Stanislas settles in Nancy as Duke of Lorraine

This idea of a life annuity may have come from Frederick Augustus of Prussia or perhaps Cardinal de Fleury, who, according to some historians, had planned it all and supported Stanislas only so that he would fail and agree to take Lorraine, but nothing is less certain. In any case, this is what resolved the situation in Europe and brought an end to the War of the Polish Succession. It was agreed that Francis III Stephen of Lorraine and Bar would marry Maria Theresa of Austria (a happy marriage that produced 16 children!) and that he would receive the Grand Duchy of Tuscany upon the death of the last of the Medici (which would happen on July 9, 1737). In exchange, he gave the duchies of Lorraine and Bar to Stanislas. Upon Stanislas' death, they would revert to the French Crown, as the king had only Marie as his heir. For France, this was an excellent deal, as it could finally legally lay claim to the rich Lorraine and join it with Alsace, conquered in the 17th century by Louis XIV. In 1737, after more than three years of war, the Treaty of Meudon was signed. Stanislas allowed himself to be persuaded to accept. He wrote to his daughter, "In the absence of Poland, I agree with you that Lorraine is the only thing I can accept" (these people talked about a duchy as one would talk about a car...). nbsp; The War of the Polish Succession ended in 1737, just as Stanislas' reign in Lorraine began.

The Benefactor: A "phantom" ruler who became beloved by the people of Lorraine

Stanislas according to an engraving from 1740 IImage chosen by monsieurdefrance via Limedia.fr.

The people of Lorraine surprised all of Europe by reacting very badly to the news. This was surprising because in the 18th century, it was not customary to listen to the people, and no one had asked the people of Lorraine what they thought about the idea of imposing a new duke on them who had no connection to them. Many people followed the carriage of Elisabeth Charlotte, the mother of François III of Lorraine, when she left the castle of Lunéville for that of Commercy, which had been elevated to a principality so that she would not have to live under the reign of Stanislas. It was there that she died in 1744. When Stanislas arrived in Nancy, he received a frosty welcome. Duke François took the Meudon Convention literally. He left absolutely nothing behind. Not a single piece of furniture. Stanislas was forced to sleep for several weeks in the Beauvau family's mansion in Nancy(now the Nancy Court of Appeal) while the completely empty Lunéville Castle was being furnished. Even the lead frieze on the roof of the ducal palace had been dismantled. Nothing remained.

Stanislas appoints Antoine de la Galaizière as his chancellor. Painting by Jean Girardet. Image selected by monsieurdefrance via Limedia.fr.

Stanislas also had to accept being a duke without power. France did not want him to consider himself a fully-fledged sovereign and wanted to bring the Duchy of Lorraine into line with the Kingdom of France. A kind of prefect was therefore imposed on the king, leaving him free to give him whatever title he wanted. The man's name was Antoine Martin Chaumont de la Galaizière. He was given the title of chancellor and shared power with Stanislas (and the king's mistress, the Marquise de Boufflers). The king had a comfortable civil list that allowed him to indulge himself by building many things and also by setting up facilities for his subjects, such as charity workshops to provide the poor with work and therefore an income to feed themselves. Hated by the people of Lorraine upon his arrival, he was unanimously mourned 30 years later, upon his death in 1766. It was a long reign, even though everyone thought that Stanislas, being over 60, would only reign for a few years. Life annuities sometimes hold surprises for the future owner...

Place Stanislas. Nancy owes what it is today to the "good King Stanislas," who reigns over the most beautiful square in the world. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: Shutterstock.

Stanislas died on February 20, 1766, in an accident. Very old (88 years old), sitting alone in front of his fireplace, barely able to see (when he went fishing, servants who loved him dearly would dive in to hook fish for him since he couldn't see them), the king wore the warm nightshirt that his daughter Marie had given him. He leaned toward the fireplace to grab a poker to relight his famous chibouque, the long pipe he had taken to smoking 40 years earlier when he was a prisoner in Moldavia. He does not see that, too close to the flames, his dressing gown catches fire. It is only later that he realizes what has happened, gets up to put out the fire and call for help, and falls into the blaze that was warming him. He dies a week later, but not without a final witty remark. Looking at a servant who was caring for him, he said, "Madam, did I have to burn in such a fire for you?" He rests in the Church of Notre Dame de Bonsecours, which he had completely rebuilt in 1737 to be his tomb. In Nancy, which he made magnificent with the three squares that were created at his behest, which are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and whose jewel, Place Stanislas, has borne his name since 1831.

Place Stanislas in Nancy with its golden railings in the rising sun / Photo chosen by Monsieur de France: shutterstock

The character of Stanislas: A humanist and epicurean prince

A generous and enlightened temperament

Beyond his title, Stanislas Leszczynski was a man of great intellectual curiosity and profound humanity. Marked by his years of exile and reversals of fortune, he developed a philosophy of life focused on charity. An accessible sovereign, he enjoyed mingling with his subjects and shunned the rigid etiquette of Versailles. His character, described as both gentle and resilient, enabled him to transform his political failures into a major cultural success in Lorraine. A prince of the Enlightenment, he firmly believed that the happiness of a sovereign depended on that of his people.

Stanislas the gourmet: At the origin of sweet legends

Photo shutterstock

Stanislas's story is inseparable from his passion for food. A great epicurean, he was not content with simply tasting; he loved to experiment. According to tradition, we owe two treasures of French gastronomy to his love of good food:

-

The invention of rum baba: Finding Polish brioche (kouglof) often too dry, Stanislas is said to have had the idea of sprinkling it with Malaga wine to soften it. This dessert was later perfected with rum by the pastry chef Stohrer, but the creative spark came from the ducal table.

-

The birth of the Madeleine: During a reception at the Château de Commercy in 1755, the Duke found himself without dessert following a quarrel in the kitchen. A young servant girl, Madeleine Paulmier, then made small golden cakes in the shape of shells according to her grandmother's recipe. Stanislas, won over, gave the young woman's first name to this sweet treat, which would become famous worldwide.

Advice from Monsieur de France: To relive this gourmet atmosphere, don't hesitate to visit Nancy and its must-see sites, where historic pastry shops continue to perpetuate the sweet legacy of the good King Stanislas.

What Lorraine owes to Stanislas: A monumental legacy

The origin and construction of Place Stanislas

A true link between the Old Town and the New Town, construction of the Place Royale (now Place Stanislas) began in 1751. Stanislas wanted to magnify Nancy while honoring his son-in-law Louis XV. Under the direction of architect Emmanuel Héré, former marshland was transformed into a classical ensemble of rare harmony. The contribution of artists from Lorraine was crucial: the artistic locksmith Jean Lamour installed his famous gilded railings and monumental fountains completed this masterpiece, which is now listed by UNESCO.

Thanks to his architectural work, Stanislas turned his capital city into an exceptional destination. To make sure you don't miss out on any of this heritage, check out our comprehensive guide to visiting Nancy and its must-see attractions.

Lunéville: The "Versailles of Lorraine"

Far from the hustle and bustle of Nancy, Stanislas made Lunéville his favorite residence. In the castle built by Leopold of Lorraine, the penultimate duke of the dynasty that ruled Lorraine for seven centuries, Stanislas established a brilliant court that attracted philosophers such as Voltaire. He embellished the castle and its gardens (the famous "bosquets"), creating an intellectual and artistic center that shone throughout the Europe of the Enlightenment.

The Arc Héré closes off Place Stanislas and leads to the magnificent Place de la Carrière / Photo chosen by Monsieur de France shutterstock

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Everything you need to know about Stanislas Leszczynski

What is Stanislas Leszczynski's official title?

Stanislas Leszczynski held several prestigious titles during his lifetime: he was first King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. After his exile and his daughter's marriage to Louis XV, he became, by the Treaty of Vienna, the last Duke of Lorraine and Bar for life.

Why is Stanislas Louis XV's stepfather?

In 1725, his daughter Marie Leszczynska married the King of France, Louis XV. This marriage, often referred to as a "Cinderella marriage," transformed Stanislas's destiny. It was thanks to this close family connection that France negotiated sovereignty over the duchies of Lorraine and Bar for him.

Who designed Place Stanislas in Nancy and why?

Place Stanislas (formerly Place Royale) was built by architect Emmanuel Héré between 1751 and 1755. Stanislas commissioned this monumental complex to honor his son-in-law, Louis XV, and to connect the medieval Old Town with the New Town of Nancy. The famous wrought iron gates embellished with gold are the work of the locksmith and artist Jean Lamour.

What culinary specialties are attributed to Stanislas?

Popular and culinary tradition links Stanislas to two icons of Lorraine gastronomy:

-

Baba au rhum: It is said that he had the idea of sprinkling Malaga wine (and later rum) on a brioche (similar to a kouglof) that was too dry in order to soften it.

-

La Madeleine: During a reception in Lunéville, he is said to have named this little cake after the servant who had prepared it, Madeleine Paulmier.

What did Stanislas of Nancy die of?

Stanislas died on February 23, 1766, at the age of 88, following a tragic accident at his home in Lunéville Castle. His dressing gown caught fire when he stood too close to the fireplace. Too old to react, he succumbed to his burns after several days of agony. His death led to the immediate and definitive annexation of Lorraine to France.

Where is Stanislas Leszczynski's tomb located?

Although his heart was laid to rest in the Church of Saint-Jacques in Lunéville, Stanislas's body lies in Nancy, in the Church of Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours. He rests there alongside his wife Catherine Opalinska in a monumental mausoleum sculpted by Louis-Claude Vassé.

What does Stanislas show on Place Stanislas in Nancy?

He points to the medallion located beneath the golden figure (recognizable by his trumpet) crowning the Arc Héré. This gesture reminds us that it was for Louis XV, his son-in-law, that Stanislas endowed Nancy with a royal square, which became Place Stanislas in 1831.

Find out more about Nancy: