French people often struggle with spoken English not because of a lack of ability, but due to cultural history, a school system focused on grammar, fear of making mistakes, and limited exposure to English in daily life.

The French paradox when it comes to English

The paradox is striking: while France is the world's leading tourist destination, the French have a persistent reputation as "poor students" when it comes to speaking the language of Shakespeare.

Lack of will? Natural difficulty? Cultural resistance? The reality is much more subtle. More and more French people speak English: 32% (dixit French Ministery of culture). That's a lot more than 10 years ago. Furthermore, the French have the same attitude towards other languages as they do towards their own: language must be respected and not damaged. As a result, for fear of making mistakes, many French people give up speaking English.

A couple sitting at a café terrace. Photo selected by monsieurdefrance.com: depositphotos.

Why French dominated the world for so long

For centuries, French was the international language. The French therefore did not have to ask themselves this question, much like the British or Americans today. Diplomacy, European royal courts, Russian intellectual elites: speaking French was a marker of power, elegance, and knowledge.

Accepting that English has taken this place is not just a linguistic change. For the French collective unconscious, it is the mourning of cultural hegemony. This protection of French is institutionalized: French is the language of the French Republic. The Académie Française monitors its use, and laws such as the Toubon Law (1994) require the use of French in advertising and audiovisual media, and English words must always be translated. This is a protective framework, certainly, but one that also creates a psychological barrier: English is perceived as a competitor, not simply as a tool.

That said, we shouldn't imagine the French as having been holed up in a linguistic bunker for centuries. The French language has always borrowed words from other languages, which proves the curiosity of the French. Italian, English, and Arabic have greatly enriched French, after Latin, of course, but also Greek to a lesser extent.

Why do the French love their language so much?

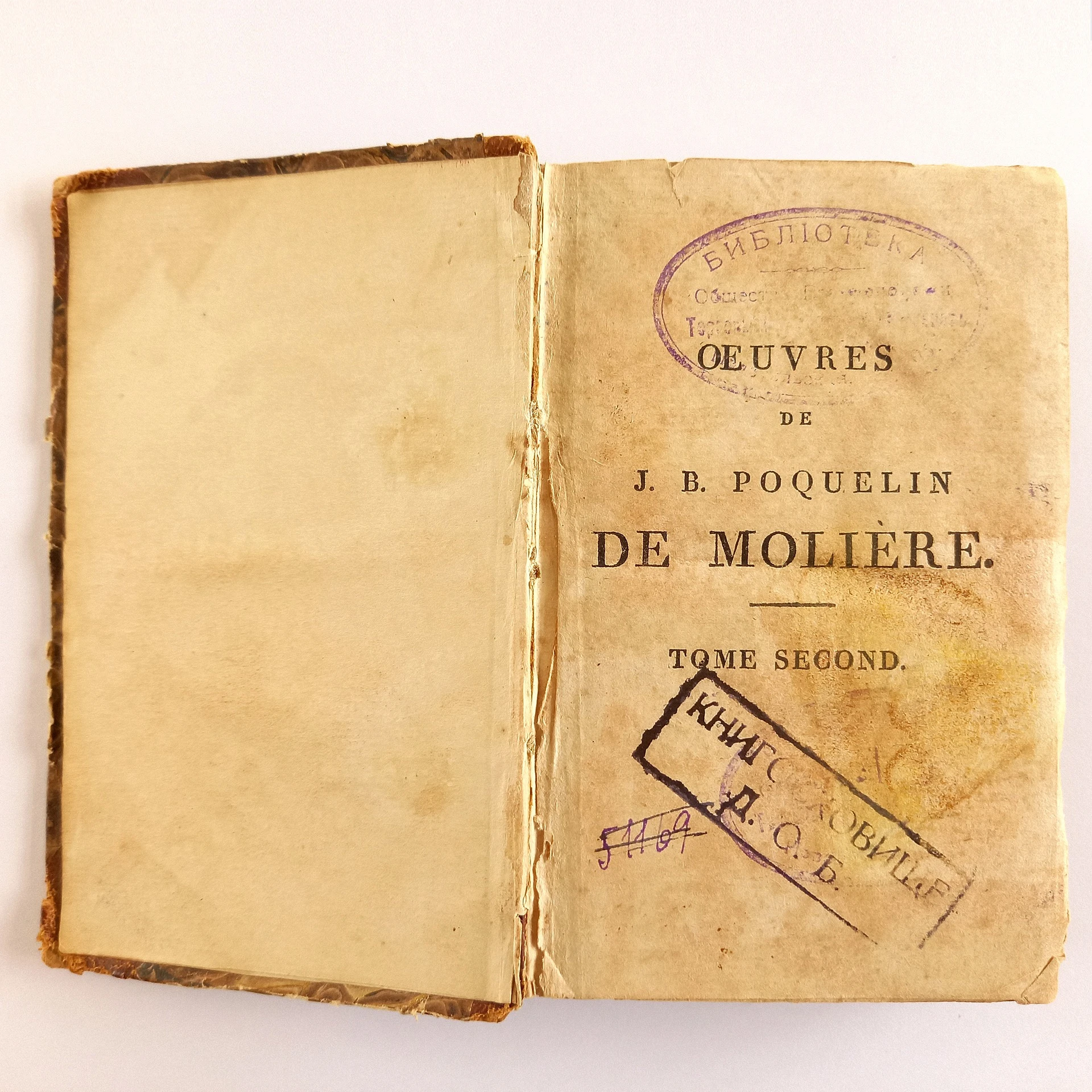

It's a fact: the French love the French language. Speaking it well is a sign of intelligence and elegance. They are immersed in the culture of "the language of Molière" and its beauty from childhood, through poems learned by heart and then the great classics of literature. Speaking French well is a real pleasure for people here.

French is nicknamed by the French as "the language of Molière" / Illustration chosen by Monsieur de France: by Myriam from Pixabay

What about tourists?

Even if they don't show it, perhaps because they are not as expressive as other nationalities, French people are very sensitive to the fact that a foreigner speaks French. If they can, they will help by correcting a word or pronunciation. This is sometimes, or even often, taken the wrong way, when in fact it is a sign of consideration. Even if you don't speak French at all, always start with "bonjour" rather than "hello" or "merci" rather than "thank you." You'll be amazed at how many doors this opens.

Why French schools did not encourage English as they should have done

In France, a country of written culture where writing is paramount, language learning has long been based on writing and grammar rather than speaking.

I remember that at school, when I was a child in the 1980s, emphasizing words was seen as a desire to show off. And above all, we practiced very little, and rarely when speaking or watching films. Only the teacher spoke English in class. And then you don't want to look ridiculous when you speak a language in front of native speakers. We think they'll laugh at us, and this deeply ingrained linguistic modesty is too often interpreted abroad as arrogance, when in fact it's mostly social shyness. It's paradoxical, because the best sign of affection a French person can show you is to correct your French. They see it as a desire to help and, curiously, do not take it the other way around.

Alain Rey, a specialist and historian, analyzes this very well. He says, "France has a pathological relationship with language errors, which are perceived as moral faults or a lack of refinement." How terribly true!

Why dubbing hinders English language learning

Image by SAAD_KURT from Pixabay

In Nordic countries and the Netherlands, children are immersed in English from a very early age thanks to original versions with subtitles. In France, dubbing reigns supreme. Major foreign productions are carried by remarkably talented voice actors, but this excellence comes at a cost: French ears are not naturally exposed to English.

Result:

-

more difficult listening comprehension,

-

stronger accent,

-

greater cognitive effort in adulthood.

The noise barrier: a real physical challenge

Beyond willpower, there is a little-known physical barrier: frequency bandwidth. According to the work of Dr. Alfred Tomatis, ENT specialist and researcher, each language has its own listening range. French is mainly between 200 and 500 hertz, while English flourishes at much higher frequencies: 2,000 or even 12,000 hertz. "The ear is not capable of analyzing sounds that it cannot reproduce," says Alfred Tomatis.

-

English is rich in high-pitched sounds and stressed syllables.

-

French is flatter, more linear, with lower frequencies.

For a French person, hearing English correctly requires retraining the ear. It can be very difficult to understand spoken English, and French people are often better at written English. Similarly, just as the French "R" is difficult for an English speaker to pronounce, certain pronunciations are very complicated for a French person (the R in particular). This also explains why the French accent remains one of the most recognizable in the world... and sometimes one of the most charming.

The richness of the French lexicon: precision rather than simplicity

Visitors are often surprised: Why so many words to say the same thing?

French favors nuance. It also loves imagery, and whenever possible, it strives to demonstrate "esprit" (a blend of humor and wit). This leads to a tendency to "embellish" vocabulary.

Whereas English gets straight to the point, French likes to qualify, clarify, and express feelings...

Simply saying that a wine is "good," for example, is almost a cultural faux pas.

It will be rather:

-

well-built,

-

balanced,

-

silky,

-

long finish.

And it works for lots of things: a person, a meal, the weather, and so on... Some see it as a legacy of the 18th century and the passion people had for describing someone in long sentences.

Here are 15 typically French expressions that are completely untranslatable.

The paradox of "fundamental French"

Good news for visitors: with 1,500 words, you can cover nearly 80% of everyday situations. The secret isn't the amount of vocabulary, but the use of polite phrases, which are the real keys to communication in France.

Conclusion: a legacy in motion

If the French sometimes speak English less well than their European neighbors, it is neither out of laziness nor rejection. It is the result of history, a demanding relationship with language, and a culture where words carry weight.

But things are changing fast.

The younger generations, raised on TV series in their original language, social media, and international exchanges, are gradually breaking through this invisible barrier. Today more than ever, the French may still have an accent... but above all, they have a sincere desire to share their culture, their cuisine, and their landscapes.

An article by Jérôme Prod’homme for Monsieur de France, written with passion and pleasure to describe France, its culture, and its heritage.

Monsieur de France is a leading French-language website dedicated to French culture, tourism, and heritage.

FAQ – The French and English

Why do the French speak poor English?

French people often speak less English for fear of making mistakes, due to an education system that has long focused on grammar and a culturally demanding relationship with the language. They often understand better than they speak.

Do French people understand English without speaking it?

Yes. Many French people understand written and spoken English, but don't dare to speak it for fear of looking ridiculous or making mistakes.

Why do Nordic countries speak better English than France?

Nordic countries make extensive use of original versions with subtitles and encourage speaking without fear of punishment. Early exposure and a lack of fear of making mistakes make all the difference.

Do young French people speak better English today?

Yes. The younger generations are making significant progress thanks to TV series in their original language, social media, travel, and exchange programs such as Erasmus.

How can you make yourself understood in France without speaking French?

Always start by saying "hello," adopt a polite and humble attitude, and use a few key words such as "please," "thank you," and "excuse me."

Illustration chosen by Monsieur de France: by Myriam from Pixabay