THE MEROVINGIANS (5th–8th century)

The world after Rome

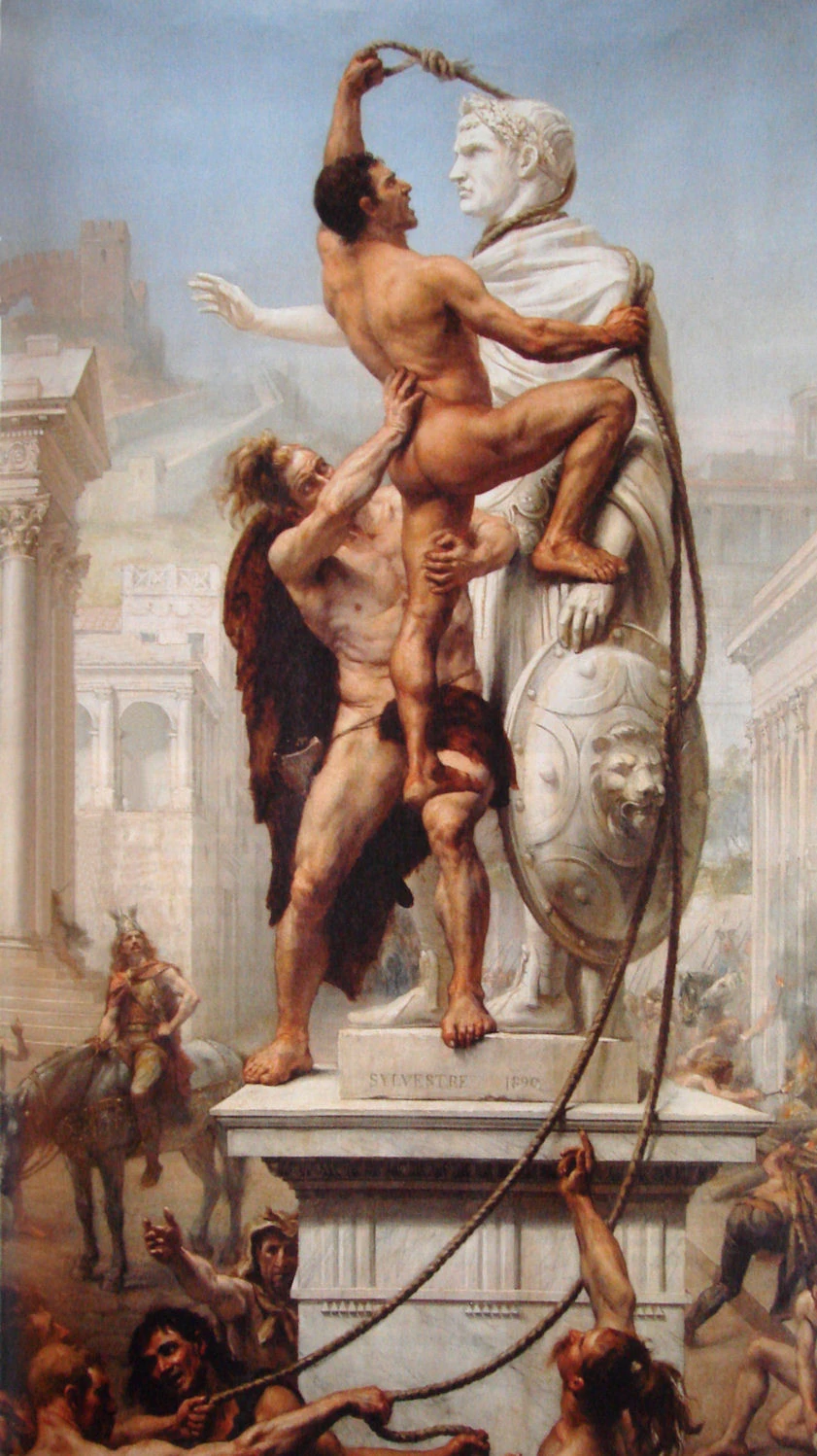

The Sack of Rome in 410, a dramatic scene painted by Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, a powerful historical representation, illustration chosen by monsieurdefrance.com.

Imagine the setting: Gaul after the fall of Rome. It's not a dusty museum, it's a field of ruins. All that remains of Roman grandeur are pieces of marble stuck in the mud. You walk through half-empty cities, come across collapsed fortifications, and wonder who's in charge—it's a joyful mess. And Roman civilization, refined, organized, which loved hot baths and mosaics so much... well, it caught a cold. Game over. Now it's the Franks. And clearly, they haven't read Seneca, they don't care. For them, what matters is strength and... hair. There's nothing worse for a Frankish king than to be bald, or worse: shaved when he is defeated. Hair is a sign of strength and virility.

With the Merovingians, we are still at the beginning of French history and the first kings of France, those who are rarely mentioned in textbooks but who laid the foundations of the French monarchy.

Clovis (466–511), the founding baptism

Clovis was initially one of the leaders of these nations that had settled and were defending their territory. But he had something that the others did not have: vision. He looked at this traumatized Gaul, he saw the bishops who were still standing, like pillars in the midst of a storm, and he said to himself: "Hey, how about we be friends?" After all, even though he is not a Christian, he notices that what still stands is the Church and its well-established structure. A link between peoples above the various barbarian kings. And BAM, baptism in Reims. That's genius. In a single gesture, he transforms himself from invader to heir. Everyone breathes easier. He becomes respectable. He is seen less as a hairy savage and more as a respectable gentleman. This is where the "France" mayonnaise begins to take shape.

The Baptism of Clovis / By Master of Saint Gilles — National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., online collection, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=311711

Brunehaut and Frédégonde

Ah, those two... you could make a Netflix series about them. Two women, two temperaments, two hatreds. Brunehaut, the organizer, the woman who understands what a kingdom is, who wants to bring order to it all. And Frédégonde... watch out. She's the flint in the boot. The one who smiles sweetly at you as she serves you your cup of wine, while her servant pours poison into your dessert. Their scheming spans forty years, forty years of family dramas, husbands who die too soon, heirs who suddenly disappear, little cousins who are "accidentally" strangled. No, these are not fictional stories: this is the real life of the Merovingians — and it is bloody. Brunehaut, clinging to power, meets a tragic end. She is condemned to be tied by her hair and hands to a galloping horse that is thrown into a field of stones. A bloody mess in the end. Horrific... But that was the norm at the time: people were cut down, their throats slit, their eyes gouged out when they were involved in political conflict. "Different times, different customs," as the old French proverb says.

The Torture of Brunehaut, a powerful historical scene illustrating the tragic end of the Merovingian queen, illustration chosen by monsieurdefrance.com.

Dagobert (603–639), the last true king

Dagobert was a serious king, yet today he is reduced to a pair of upside-down pants—it's almost criminal. Dagobert was the last Merovingian to truly reign. After him, kings were content to reign in appearance only. They had the title, they had long hair... but they no longer had the power to make decisions.

Charles Martel (676–741), the true uncrowned king

And then we come to a curious character: Charles Martel. He is not a king. He does not wear a crown, he does not have a fancy title, but everyone knows that he is the boss. When trouble arises, he is the one who responds. When there is territory to defend, he is at the front, not behind. And in 732, at Poitiers, he sent the invaders from Spain back south. Let's be clear: this victory made Charles Martel the hero of the moment. He was nicknamed "le martel," the hammer, because the victory was so complete. We sense that a dynasty will arise from this man. We will have to wait another two generations. But Charles doesn't care, he has gained immortality.

Charles Martel during the Battle of Poitiers/image selected by Monsieur de France: Charles de Steuben — Source unknown, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=363367

Pepin the Short (714–768), the guy who asks THE killer question

Pépin is Martel's grandson, and he has inherited his political acumen. He looks at the Merovingian kings, with their sacred hair, their noble airs, and above all... their growing uselessness, and he says to himself: "Well, there's something wrong here." However, he doesn't have much to impress with: he is small. So small that he was nicknamed "the short one." But still, he has a brain, he knows how to fight, and he asserts himself. So much so that he overshadows the Merovingian king, who has a hard time seeing the light. And he dared to ask the pope THE question — the one that changed the country's destiny: "Should one be king because one is descended from a king... or because one truly governs?" And Rome, never lacking in practicality, replied: "Because one truly governs."

At this, Pepin rubs his hands together. The Merovingians lose their crown and Pepin becomes king. Charles III, the last descendant of Clovis, is tonsured but his life is spared, and he is locked up in a monastery. Game over.

Childeric III at the moment of his tonsure / Painting chosen by Monsieur de France: By Didier Descouens — Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81225631

Why are we changing dynasties?

Because the Merovingians no longer ruled. They existed, they posed for tapestries, they looked like kings—but they ruled nothing. Power lay elsewhere, in the offices of the mayor of the palace. And in a world that is in turmoil, collapsing, recovering, there is a need for people who make decisions. Pepin belongs to that category. The Carolingians enter the scene because the country needs kings who govern, not kings who doze.

THE CAROLINGIANS (751–987)

Coronation of Pepin the Short in Saint-Denis (oil on canvas by François Dubois, 1837 / Image selected by Monsieur de France By G. Garitan — Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35561914

The Carolingian dynasty, made famous by Charlemagne, is one of the great periods of the French monarchy: it was then that the list of French kings began to resemble a true continuous history.

The dynasty that brought its country out of ruin

While the Merovingians put France on track, the Carolingians lifted the locomotive with their bare hands to get the country moving again. Under their rule, paperwork was organized, roads were repaired, clerics were educated, and treaties were signed with foreign powers. In short: civilization began anew. And it all started with... Pepin the Short.

Artist's impression of Pepin the Short (painting by Louis-Félix Amiel commissioned by Louis-Philippe for the Museum of French History in 1837 / image chosen by Monsieur de France By Louis-Félix Amiel — Source unknown, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=954244

Pepin the Short (714–768), the first Carolingian

So he, with his small stature and monk-soldier energy, will give the country momentum and direction. It's almost as if he's running around with a hammer in his hand to fix whatever needs fixing. He's not a king who takes naps. He's a king who shakes up the kingdom. He is preparing the ground for someone even greater than himself. He had several children with Berthe, his wife with the big foot. You will notice that I do not use the word "foot" in the plural. If you think about it, the children must have been small like their father, with one big foot. That gives you pause, doesn't it? One of them stands out in history, and the chronicle tells us that he was tall in stature: Charlemagne.

Charlemagne (742–814), the man on the move

Charlemagne : Par Albrecht Dürer — The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN : 3936122202., Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=556878

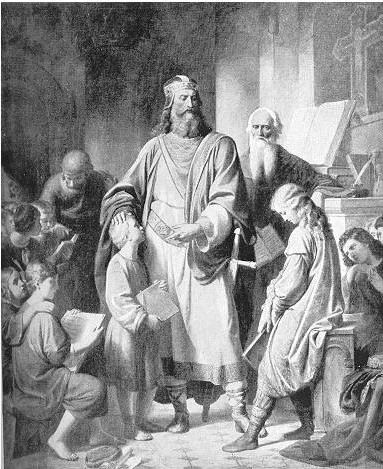

Ah... Charlemagne. "Carolus magnus" in Latin, meaning Charles the Great. When you hear his name, you immediately picture a large figure, a tireless horseman, a man who spoke several languages (but wrote very poorly)... a historical figure who is still known throughout Europe today. He had many qualities, the foremost of which was that he knew how to surround himself with knowledgeable people. Charlemagne was a conqueror, sometimes a bloody one. The Saxons, for example, were massacred. But he was also a builder. He protected monasteries, had manuscripts copied, and improved education. The famous "Carolingian Renaissance" was his doing. You could say that Charlemagne pressed the "culture" button again in Europe. Legend has it that he rewarded the students of the schools he founded and scolded those who did not work hard enough, no matter how noble they were. Charlemagne was so often victorious in war that he owned almost all of Europe. As a result, on December 25, 800, the pope placed an imperial crown on his head. Charlemagne hadn't asked for this, but it still made quite an impression. On that day, the West once again had an emperor. And he was a Frank, not a Roman. That changed everything. By the end of his reign, his empire stretched from present-day France to eastern Germany and also included half of Italy, among other territories. All the monarchs in European history would dream of reviving Charlemagne's empire.

Charlemagne congratulates the deserving student and lectures the lazy one. Engraving after Karl von Blaas, 19th century, via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis the Pious (778–840), the overly kind son

Louis, on the other hand, is not his father. He lacks presence and authority. He is a kind man, the type who wants to please everyone—and inevitably satisfies no one. With his sons fighting over the succession, the kingdom is falling apart like a worn-out shirt.

The result? The famous Treaty of Verdun in 843. Knock, knock, knock, we cut Charlemagne's crown into three pieces. We distribute the pieces. And then, inevitably, things start to go haywire. So we have three kingdoms after Charlemagne's empire. On the left is Francia occidentalis, on the right is Germania, and in the center is a sort of strip stretching from the shores of the North Sea to Rome. From the present-day Netherlands to the middle of present-day Italy.

And then... the crumbling

After Louis, we lose track a little with a succession of less memorable kings—guys who weren't necessarily bad, but weren't particularly remarkable either. Some made headlines, such as Louis III (863-882), not necessarily because he won a fierce battle against the Vikings in 879, but because he was the first Frankish king to die a foolish death. In his haste to catch a young woman who was fleeing from him, as he tried to ride his horse into the house where the girl had taken refuge, he did not see that the lintel of the door was too low for him to pass through on horseback and smashed his head on it. The same thing would happen several centuries later to another king named Charles VIII, but we have time, as we are only in the year 882. Nevertheless, with the last Carolingians, power became increasingly local, lords regained importance, and the monarchy ran out of steam. The last was Louis V, nicknamed "the Slacker" (another not very nice nickname). He came to the throne and did not stay there long. He died young, without an heir. And that was the moment to take stock. Who did the crown belong to? To the Carolingian family? Or to whomever the kingdom's nobles chose? Take a guess...

Louis V, the last Carolingian imagined by Louis-Félix Amiel — art.rmngp.fr, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3323315

Why are we changing dynasties?

Because the Carolingians, after Charlemagne, ran out of steam. They failed to transform Charlemagne's stroke of genius into a solid tradition. Power became fragmented. The lords regained local control. And at the top, there were no more great men. So the kingdom turned to a new candidate, a strong, reliable man with a strong foothold in Paris: Hugh Capet.

The first Capetians (987–1328)

Reims Cathedral, where French kings were crowned / Photo by monticello/Shutterstock

With the Capetians, we enter what teachers often refer to as the "long duration": the Capetian dynasty ruled France for more than eight centuries, making it the core of the list of medieval French kings.

A dynasty that is advancing slowly... but surely

The Capetians were not flashy kings or hot-tempered volcanoes. They were kings who moved slowly, like an ox plowing a field—but the furrow they left behind was solid. They would transform a fragmented France into a united kingdom. And it all began with a man who was not particularly spectacular, but very clever: Hugh Capet.

Coronation of Hugh Capet (941-996) in 987. Illumination from a 13th- or 14th-century manuscript, Paris, BnF, ms. français 2815, fol. 58v. Gallica.fr

Hugh Capet (940–996), the first in a very long line

The year is 987. Everyone is looking at the throne, and no one seems truly unchallengeable. So the kingdom's nobles say to themselves: "Well, Capet... he's not flamboyant, but he's stable. He's reassuring. He knows the right families. He has the right alliances. Let's take him." Capet is so named because he is a lay abbot and often wears the cape of his office. He is close to the Church, which supports him and allows him to assert himself while playing on the divisions between the nobles of the kingdom.

Hugh Capet ascends to the throne. And above all—above all!—he establishes a very simple rule:

"The king will be my son."

Hugues Capet / Artist's impression by Charles de Steuben — [1], Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71381

No more folkloric successions, no more aunts and cousins waking up at 4 a.m. thinking, "Hey, why not try my luck?" The coronation of the King of France became a national ritual, which was first performed during the lifetime of the previous king to avoid controversy, then, once the Capetian dynasty was firmly established on the throne, the new king was crowned upon the death of his predecessor. This continued from father to son for more than three centuries before passing to cousins in the absence of direct heirs.

Louis VI (1081–1137), the one who said "stop" to the barons

Louis VI, known as "the Fat" (not very nice, we could have said "the Strong"), was fed up with these petty local lords who ruled their own little fiefdoms and extorted money from travelers. So he went in head-on, with troops and determination, and restored order. It was the king who began to show that France was not a mosaic of petty chiefs—it was a kingdom with a real leader.

Philip Augustus (1165–1223), the one who kicked the English's butts

The Battle of Bouvines / By Unknown Author — This image comes from the Gallica online library under the identifier ARK btv1b84472995/f514, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3967073

At that time, much of France was under English influence—thanks to William the Conqueror and his little invasion of 1066. But Philip Augustus was not going to take this lying down, and in 1214, at Bouvines, he dealt a crushing blow to the English and their allies.

That day was not just a military victory: it was a moment when the people, the nobility, and the clergy agreed on one thing:

"He is our king."

That was when France began to recognize itself in its monarchy.

Saint Louis (1214–1270), the king under the oak tree

Louis IX or Saint Louis, based on an illumination from Jean du Tillet's Recueil des rois de France (c. 1547), BnF. via gallica.fr

Louis IX, known as Saint Louis, was a deeply religious king. He even went to extremes, persecuting Jews and Cathars, in short, anyone who did not follow the Church's teachings. But he was not just a mystic in his ivory tower. He laid the foundations for the French judicial system that lasted until the French Revolution. Justice was administered in the name of the king. He was also the first to do so, according to the chronicle, under an oak tree, surrounded by his people. Is this completely accurate? Perhaps the scene has been slightly embellished... but the spirit of it is true. Saint Louis was also responsible for numerous constructions, including castles, the launch of cathedral building projects, and the famous Sainte-Chapelle, which he had built to house the relics of Christ. Engaged in the Eighth Crusade, he died after a 43-year reign in Carthage on August 25, 1270.

The Sainte Chapelle has 670 square meters of stained glass windows. Photo selected by Monsieurdefrance.com: depositphotos.com

Philip the Fair (1268–1314), the Iron King

And then comes Philip the Fair, with his cold stare and unwavering jaw. Not the type to laugh at banquets. He imposes royal authority with a firm hand, changes the currency when he wants to fill his coffers, plunders the Jews, taxes the clergy, defies the pope, and above all... attacks the Knights Templar.

Philip the Fair By Unknown Author —. National Library of France, Manuscripts Department, Latin 8504., Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=110822836

Ah, the Templar affair...

On October 13, 1307, the Knights Templar were arrested throughout France in a swift operation orchestrated by Philip the Fair. Their Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, ended up at the stake in 1314. It is said that before he died, he uttered these terrible words to Pope Clement V and King Philip: "Within a year, I will summon you to God's court!" And what is striking is that in the months that followed, the pope died... and then the king died too. Pure coincidence or divine justice? We'll let you decide. In any case, Philip IV shares with Henry II and Louis XV's heir apparent the distinction of having fathered three sons who would reign in turn without having any descendants on the French throne.

The Torture of the Knights Templar/ Image selected by Monsieur de France: Giovanni Boccaccio (De casibus virorum illustrium), translated into French by Laurent de Premierfait (Des cas des ruynes des nobles hommes et femmes), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Why are we changing dynasties?

Because Philip the Fair left behind three sons... who died without male heirs. The direct Capetian line died out. And when the question arose, "Who will be king?", England stepped in and said, "Ah, but we have a small family claim through the women..."

And here, sorry English: Salic law. An old Frankish custom that was brought out for the occasion and which says: "No crown for ladies." Others say "lilies don't spin spindles." In short, it has to be a man with a pair of balls...

The Battle of Poitiers, one of the famous battles of the Hundred Years' War / Image chosen by Monsieur de France: By Loyset Liédet — no source, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=344693

So, they chose a French cousin of the last direct descendant of the Capetian dynasty. His name was Philip of Valois. Among the English, this caused great anger among Edward III, who was the king's grandson and therefore closer in terms of genealogy, but through the female line. He decided that he was also king of France. The result: the Hundred Years' War. What an atmosphere...

The VALOIS (1328–1589)

The kings of France from the Valois dynasty ruled during the Hundred Years' War, the time of Joan of Arc, the Renaissance, and the Wars of Religion: nothing less.

Philip VI (1293–1350), the unwitting trigger

Double coronation of Philip VI and Joan of Burgundy in Reims, in 1328. source gallica.fr BNF

Philippe de Valois ascended to the throne because France refused to allow a foreign king, especially an English one, to reign through maternal descent. The famous Salic law was therefore invoked. This old Frankish custom, which everyone had forgotten, states that land cannot be passed on through women. And the kingdom of France is land for the lawyers who defend this point of view. Edward III of England, grandson of Philip the Fair and nephew of the last king of France, was therefore overlooked, despite his connection to the French through his mother, Isabella of France, and therefore through women. Instead, Philip of Valois, cousin of the last king, was chosen. Needless to say, Edward III did not accept this idea and set out to conquer what he considered his inheritance. Thus began the Hundred Years' War, not over a question of borders, but over a question of dynastic pride and national identity. Philip VI did not have much luck during his reign: he inherited a conflict he did not want, and he would pay the price for it.

Charles V (1338–1380), the cool head

When Charles V arrives, he quickly realizes that fighting the English head-on is foolish. He changes his strategy: he suffocates the enemy, deprives them of resources, and buys their loyalty. He was a king who won more through intelligence than violence, and his most valuable ally was Bertrand Du Guesclin. Together, over the years, they recaptured lost territories and, above all, restored confidence to a France that was faltering.

Presentation of the constable's sword to Bertrand du Guesclin. Miniature from the Grandes Chroniques de France attributed to Jean Fouquet, circa 1455-1460, BnF, Fr.6465.

Charles VI (1368–1422), the Glass King

The reign begins well—he is even called "Charles the Beloved." But then his mind begins to unravel. He screams that he is made of glass and must not be touched, he no longer recognizes his loved ones, he gets lost in his own palace. A mad king on a fragile throne: it's the perfect recipe for civil war. Armagnacs against Burgundians, brothers against brothers — and meanwhile, England takes advantage of the situation to regain a foothold in the kingdom.

Joan of Arc (1412–1431), the flame in the night

Illuminated initial known as Joan of Arc with the Standard, forgery produced at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Paris, National Archives.

Just when all seems lost, with the kingdom on the brink of collapse, a young girl from Lorraine, Joan, aged 17, with burning conviction, appears. She rallies the future Charles VII, lifts his spirits, breaks the siege of Orleans, and restores hope to a people who had lost faith. She died burned alive, but her death became a founding myth—that of a France which, sometimes, is saved by its people.

Louis XI (1423–1483), the spider with nimble fingers

A small, wiry king, nervous, not very spectacular, rarely amiable—but incredibly effective. Louis XI centralized, controlled, maneuvered, and set traps for nobles who were still too independent. We always imagine him silently squinting as he watched his enemies. This king was not flamboyant, but he consolidated the kingdom in a way that had a profound impact on the state. For the record, we owe him the invention of the postal service in France. His son Charles VIII married Anne of Brittany and united the old duchy with France before dying foolishly by hitting a door lintel while running to meet a friend. We are but small things.

Francis I (1494–1547), the Renaissance personified

François I by Jean Clouet — Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30275305

With Francis I, things took a different turn. He was quite a character. He embodied the spirit of the Italian Renaissance: arts, literature, architecture, elegance. He developed the French language, making it mandatory in legal and civil documents in 1537, brought Leonardo da Vinci to France, and built Chambord and Fontainebleau. Highly ambitious, he in turn launched himself into the Italian Wars, which ended in failure despite the famous victory at Marignan in 1515. He wanted to become emperor against his Spanish rival, but he did not succeed and was even taken prisoner at the end of a battle. Flamboyant but not always gifted enough to fulfill his desire for glory, he nonetheless remains one of the kings who shaped France. He gave France a brilliant cultural identity, an aesthetic personality that is still evident today.

Chateau de Chambord Photo by Tsomchat/Shutterstock

Henry II (1519–1559), the good years before the storm

Henry II was a strong, energetic, and very chivalrous king, but also stubborn. During his reign, religious divisions began to widen significantly. Protestants—also known as Huguenots—were no longer just a few isolated bourgeois: entire communities, influential nobles, and sometimes entire cities were converting. Henry II refused to believe it. For him, the kingdom was Catholic and must remain so. He repressed the Protestants with the firmness of a man convinced he was right—which, of course, only fueled hostility and opposition. This was the beginning of religious violence, provocations, pamphlets, attacks on processions, symbolic and real burnings at the stake—enormous tension rumbling like a storm on the horizon. And in a tragic irony, just when the kingdom needed a strong leader, Henry II died in a tournament, pierced in the eye by a broken lance, leaving the kingdom in the hands of sons who were too young... at the worst possible moment.

The fatal tournament imagined in Germany / By 16th century German print, anonymous — "Catherine de Medicis and Henri III" Historia, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10347790

The sons of Catherine de Medici: three kings and tragedy

François II, Charles IX, Henri III—three successive sons, three fragile kings, three unstable reigns. And not a single male heir to continue the dynasty. During their reigns, the Wars of Religion flared up. Catholics against Protestants. And on August 24, 1572, night fell on Paris and... the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre transformed the capital into a religious bloodbath. Blood flowed in the gutters, and hatred left a lasting mark on the French heart.

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in Paris in 1572 / By François Dubois / Wikicommons

Henry III (1551–1589), the end of the Valois dynasty

Henri III / Par François Quesnel — https://www.meisterdrucke.fr/fine-art-prints/Fran%C3%A7ois-Quesnel/63773/Portrait-d%2639%3BHenri-III.html, Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72999

Henri III, the last Valois, ruled amid constant tension. A fanatical monk, misnamed "Clement," eventually assassinated him by stabbing him in the stomach. Before dying, Henry III did something crucial: he named his successor. And this successor was not a Valois, nor a direct Capetian... he was a Protestant cousin: Henry of Navarre.

Why are we changing dynasties?

Because there were no more direct male heirs among the Valois. And because the crown could not be passed down through women, the cousin branch was chosen. The problem was that Henry of Navarre was Protestant. Part of France cries out, "Never!" But he responds with reconciliation, patience... and the famous phrase, "Paris is well worth a Mass."

The Bourbons arrive.

On his deathbed in Saint Cloud, Henry III named his cousin Henry of Navarre, a Protestant prince, as his successor / By Anonymous 16th century tapestry — "Catherine de Medicis and Henry III" Historia, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10347879

The BOURBONS (1589–1848)

The kings of France from the Bourbon dynasty, from Henry IV to Louis-Philippe, carried the French monarchy to its end, amid glorious majesty, political fiascos, and the French Revolution.

Henry IV (1553–1610), the king who reconciled

Henry IV By Frans Pourbus the Younger — [1], Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146364373

Henri de Navarre arrives in a kingdom ravaged by religious wars. France is divided between Catholics and Protestants, and Henri is a Protestant... on paper. But he has something that very few kings have had: a sense of appeasement and a taste for the people. He understood that to rule France, he had to reduce hatred rather than stir it up. That is why he converted to Catholicism—perhaps not out of deep conviction, but out of political wisdom and love for his country. And he uttered the now proverbial phrase: "Paris is well worth a Mass."

The abjuration of Henry IV, July 25, 1593, in the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Meudon Museum of Art and History, inv. A.1974-1-6.

Henry IV then focused on what his kingdom had been lacking for 40 years: bread, agriculture, prosperity. He wanted every French person to be able to "put a chicken in the pot on Sundays." This was not populism—it was a national program. He restored peace with the Edict of Nantes, which granted civil and religious rights to Protestants. It must be said that he was also a king who adored women, an inveterate seducer, a man with a tender sense of humor—but when it came to elegance... many of his contemporaries noted that he smelled a bit like a goat, and not just after hunting. He was assassinated in 1610 by Ravaillac. It was an absurd, brutal death, a national tragedy. France may have lost its most humane king.

The assassination of Henry IV engraving / Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1360989

Louis XIII (1601–1643), the silent one, and the cardinal

Louis XIII is shy, insecure, and introverted. It must be said that he had difficulty asserting himself in the face of his mother, Marie de Medici, who preferred his brother Gaston and considered him an idiot. He is not a man who speaks loudly; in fact, he stutters, but he has the intelligence to surround himself with capable people. He found an alter ego: Richelieu. The duo worked like a machine to recentralize the state: they broke the power of the great nobles, put an end to duels, and imposed royal law. Little by little, the kingdom emerged from the turbulent aristocracy and entered the era of the modern state. Louis XIII was not a flamboyant king—he was efficient, consistent, determined, and discreet. We already owe him a France that was better governed, better administered, and free of feudal turmoil. And above all: France learned to obey the state rather than the barons.

Louis XIII Crowned by Victory, oil on canvas by Philippe de Champaigne, 1635, Louvre Museum.

Louis XIV (1638–1715), the sun that burns everything

Louis XIV in coronation robes/ By Hyacinthe Rigaud — wartburg.edu[dead link], Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=482613

Ah... Louis XIV. The most famous. The boy who was almost crushed by the nobility during his childhood (the Fronde) and who then retaliated with a political masterpiece: he locked the nobles in a palace. Versailles is not an architectural fantasy—it is a gilded cage. The nobles fought there for proximity to the king, for a glance, for a stool, for a smile. And meanwhile, real power remained in the hands of the sovereign. Louis XIV reigned for so long—72 years!—that the French ended up thinking that absolute monarchy was natural. He shines through war, diplomacy, art, dance, staging, but also through pride. He is both genius and concrete: splendid and sometimes suffocating. With him, the kingdom becomes a permanent spectacle — but a spectacle governed with a firm hand.

Gardens and Palace of Versailles / photo Vivvi Smak/Shutterstock.com

The French people of the time were aware of the downside of Louis XIV's glorious reign. In the countryside, people were starving. In 1685, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to the persecution of Protestants and their exodus, particularly to what is now Germany. France was on the brink of collapse at the end of the reign, but it held on.

Louis XV (1710–1774), ambiguity, charm, and doubts

Louis XV, long considered the most handsome man in his kingdom, in coronation robes: By Hyacinthe Rigaud — Source unknown, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1751541

Louis XV ascended to the throne at the age of five. He was a child king, a little boy whom everyone looked at with affection. People said, "He will be the Beloved." And at first, he was. But Louis XV was a man who mistrusted his power and did not like himself as king. He was shy, indecisive, and doubted himself. On the other hand, he loved love—and women loved him. His mistresses played an immense political role, notably the Marquise de Pompadour. He was accused of allowing his favorites too much influence, but this overlooks the fact that Louis XV was a sensitive, instinctive, and sometimes fragile king. He reigned for a long time, trying to keep the peace, but he allowed himself to be drawn into continental wars, notably the Seven Years' War, and lost many colonies across the ocean, foremost among them Canada and India. Firmly rooted in monarchical principles, particularly in his dealings with Parliament, and completely deaf to the philosophers of the Enlightenment, during his reign the monarchy lost in majesty what it gained in intimacy—and the revolution was already brewing.

Louis XVI (1754–1793), a man of good will in a storm

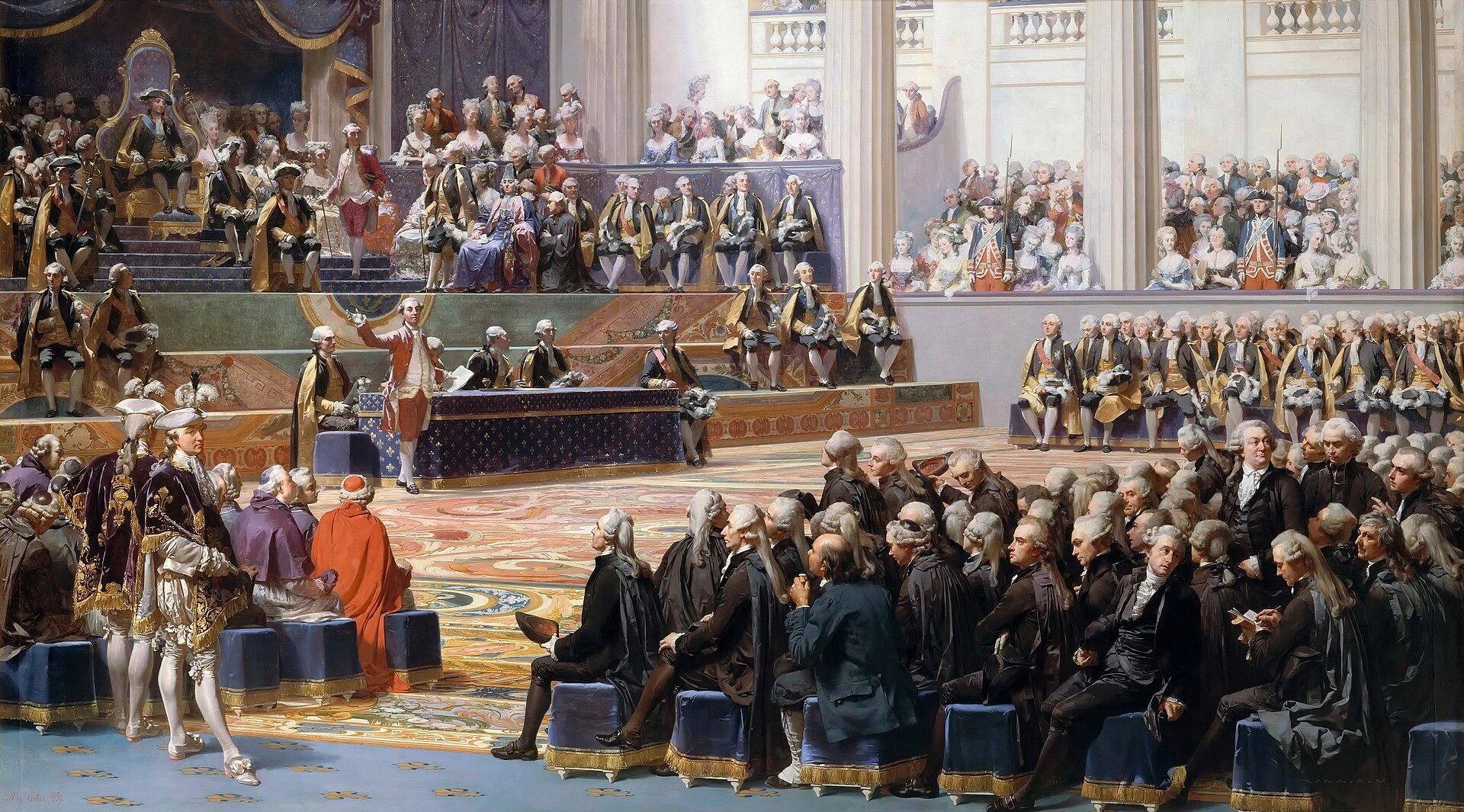

Louis XVI on his throne at the opening of the Estates General, the beginning of the French Revolution, May 5, 1789, Auguste Couder, 1839, Museum of French History (Versailles).

Louis XVI is a sincere, honest, almost shy man, a lover of locksmithing, and a good husband (which is rare in his caste). But he arrived too late. He inherited a kingdom that was financially exhausted, politically unstable, and in philosophical turmoil. He wanted to do good—but he lacked the political sense required for his role. Marie Antoinette was young, misunderstood, awkward, and mocked. The royal couple was tragic: fundamentally kind, but crushed by history. The Revolution breaks out. The monarchy collapses. Louis XVI is guillotined in 1793. His death is a profound turning point in French history—the king dies, the citizen is born.

The Death of Louis XVI/ By Desfontaines/Swebach — Museum of the French Revolution, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65041409

Louis XVIII (1755–1824), the cautious return

The king's head was cut off... and yet, the king returns. Louis XVIII returns to the throne after Napoleon. But he is not an arrogant monarch. He arrived as a tightrope walker. He understood that France was no longer the France of 1789. He accepted a constitutional charter. He governed with chambers, deputies, and a sometimes hostile press. Louis XVIII was a reasonable, calm king who sought stability rather than revenge.

King Louis XVIII in his study at the Tuileries, painting by François Gérard, Château de Maisons-Laffitte, 1823. Photo by Benjamin Gavaudo — https://regards.monuments-nationaux.fr/fr/asset-70082, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84451904

Charles X (1757–1836), the reactionary

Charles X wanted to turn France back to the past. He was too monarchist for his time, too absolutist, too attached to privileges. France grumbled, then roared, then overthrew his reign during the Three Glorious Days of 1830. Often compared to a pear, Charles X fell like overripe fruit.

Charles X was the last to be crowned King of France in Reims / painting by François Gérard — http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/g/gerard/, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1473229

Louis XIX (1775–1844), the twenty-minute king

Yes, he existed. Louis-Antoine of France. King of France for... the time it took Charles X to abdicate and for him to abdicate in turn. About twenty minutes. The shortest reign in our history. We didn't even have time to be for or against it.

The Orléans

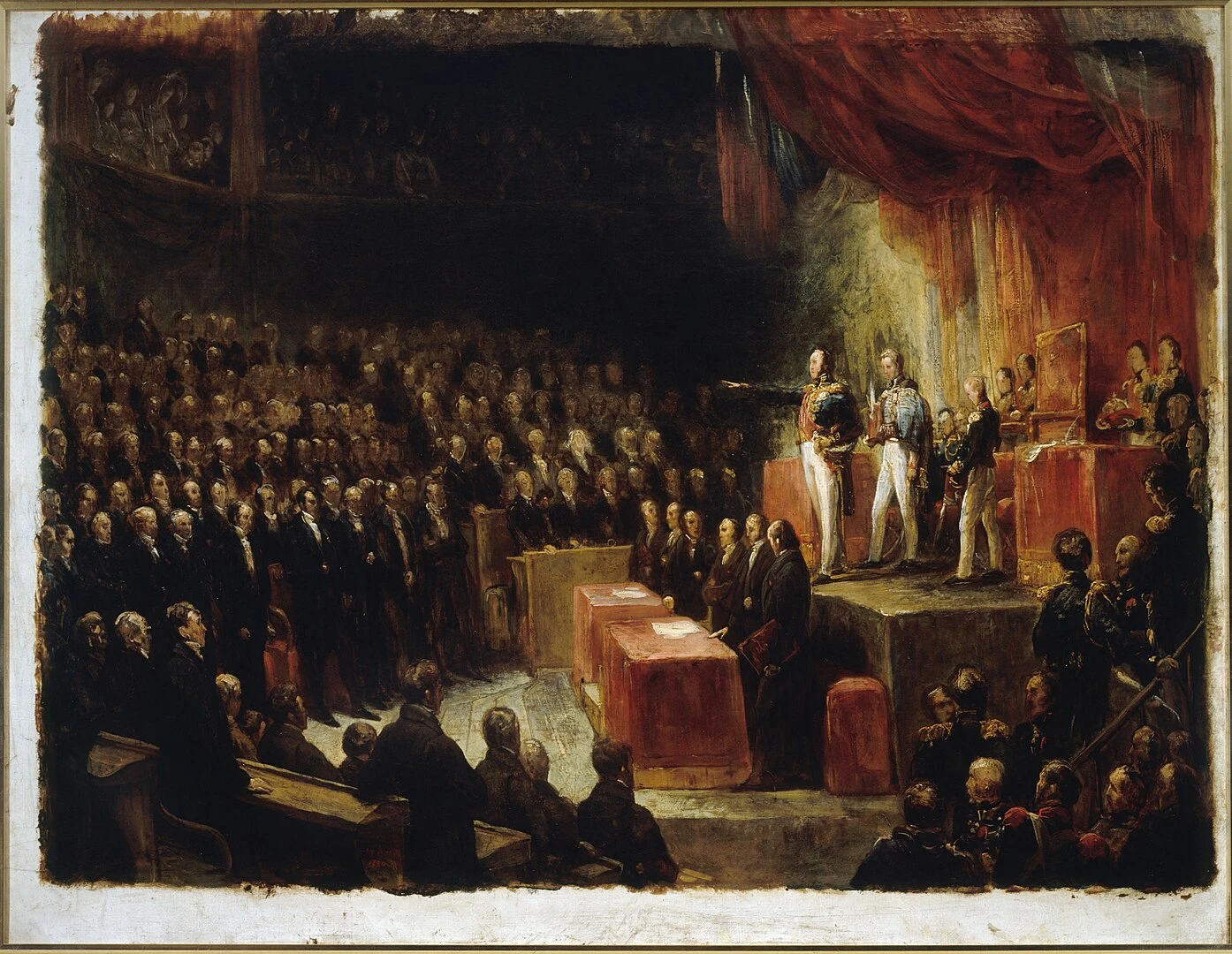

Louis Philippe takes the oath before the chambers By Ary Scheffer — Paris Musée CarnavaletPublic domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=100168910

Louis-Philippe (1773–1850), the citizen king

Louis-Philippe was a different kind of king: bourgeois, fond of umbrellas and sidewalks, with an official portrait depicting him in simple attire. He embodied an almost republican monarchy, where the king was more like a president than an absolute sovereign. But the people ended up wanting more, the bourgeoisie took power, the monarchy died out... and France slid towards a republic.

CONCLUSION

There you have it. You have traveled through fifteen centuries of history with kings who cried, loved, killed, prayed, swore, conquered, reigned, failed, and left behind a France that remembers. Obviously, this is a very simplified version, and I invite you to read more to learn more and, above all, to understand better. What is certain is that the French monarchy is not a series of dusty portraits: it is a gallery of flamboyant, fascinating, tragic, sometimes funny, sometimes terrible characters—but always deeply human, and they made France.

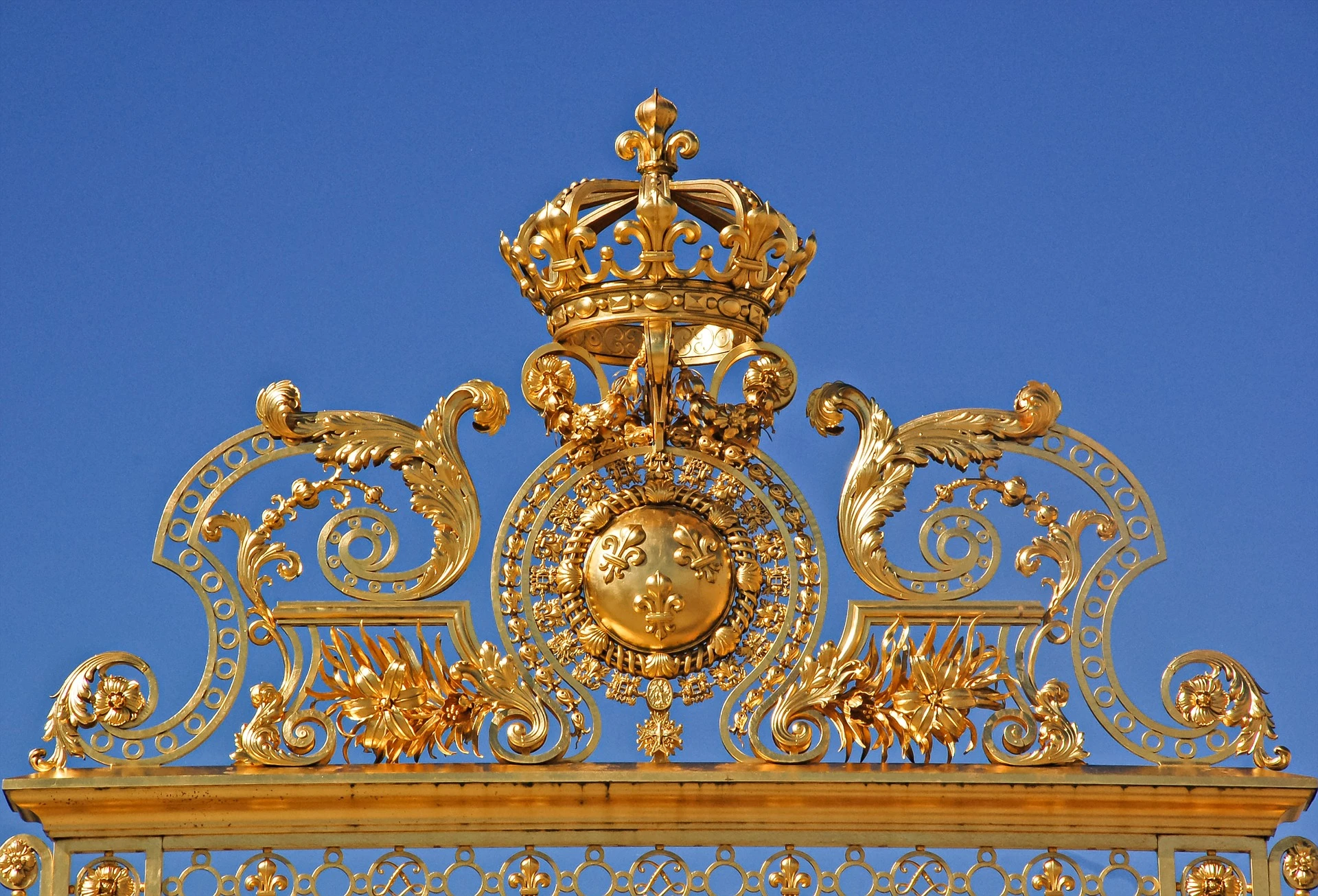

The gold-leaf gate bearing the French coat of arms that closes off the main courtyard at Versailles / photo chosen by Monsieur de France: by Rodrigo Pignatta from Pixabay

FAQ — The questions we really ask ourselves about the kings of France

Which French king reigned the longest?

Louis XIV — the Sun King — ruled for 72 years, one of the longest reigns in world history. When he died, an entire era died with him.

Which king ruled for the shortest time?

Louis XIX, who “reigned” for about 20 minutes in 1830. Blink… and you miss his monarchy.

Which king changed European culture the most?

François I. He brought Renaissance culture to France, invited Leonardo da Vinci, promoted the arts, architecture and the French language.

Which king was considered truly brilliant?

Charles V, “the Wise.” He preferred strategy and knowledge over violence. Under him, France strengthened quietly but decisively.

Which king was the most romantic (or scandalous)?

Henri IV, known for his charm and many mistresses — and for promoting tolerance with the Edict of Nantes.

Why did the French monarchy collapse?

Because of a combination of financial crisis, social inequality, Enlightenment ideas — and the storm of the French Revolution, which transformed subjects into citizens.

What makes French monarchy different from British monarchy?

In France, the monarchy ended in the 19th century and was replaced by the Republic. In Britain, it evolved but survived. The French kings disappeared — but their history became part of world heritage