Summary of the article:

In French, choosing between “tu” and “vous” is never just grammar — it expresses closeness, respect, and emotional distance. “Vous” can be a graceful way of honoring someone, while “tu” opens the door to familiarity and equality. Using “vous” doesn’t remove affection — it can even carry tenderness and dignity. Switching to “tu” often happens naturally or through the beautiful phrase: “On peut se tutoyer ?”. If you begin with “vous” and let the French person guide you, you’ll never go wrong. Mastering these two little words means understanding not only the French language, but French culture itself.A specificity of French: two forms for “you”

A specificity of French: two forms for “you”

English has only one “you”, and that often surprises foreigners who are learning French.

They often ask:

“But why do you have two different ways to say ‘you’?”

Because the French language likes nuance. It likes to let things be heard between the words. It allows you to distinguish closeness and distance simply by conjugating a verb. English cannot say “I respect you” just through the choice of pronoun — French can. Using vous is a kind of linguistic opportunity, as you will see.

The national flag on the front of a town hall in France / Image by JackieLou DL from Pixabay

When “vous” is not necessarily distance, but delicacy

Many foreigners think that vous is cold. They are wrong. It is first of all a way of greeting you when you are not yet known to the speaker, of showing respect, and of signalling that each person has their position in a discussion or interaction. Later, moving to tu will mean that you know each other and that you like each other enough to go beyond the fact of not knowing each other.

And then, vous can be a way of saying to someone: “I respect you, I value you.” It is, in that sense, an elegant gesture which naturally applies to someone who is perceived as a little “above” you: an older person, a superior.

When we say vous, we give the other person a kind of symbolic territory. We do not impose ourselves. We touch carefully, like knocking gently on a door.

Vous is not a wall: it is a velvet curtain made of language.

When “tu” is a spontaneous opening

It is easier to use the informal “tu” with someone your own age or at a party / Photo chosen by Monsieur de France: depositphotos

Conversely, tu opens the door. It brings people closer, creates a link, warms things up.

It says: “I let you come into my space.” It also means: “we are on equal footing.”

But be careful: this tu is not automatic; it is not like in English where everyone is “you”. In French, it is reserved for people who are close to you, whom you know, or with whom you feel a natural closeness — for example young people among themselves. Beyond that, French tu must be earned, if I may say so, and it appears when two people did not know each other and a bond has formed.

Using tu too quickly can give the impression of forcing intimacy.

Like getting too close to someone you haven’t really been introduced to yet.

A real story: using “vous” with a friend for 30 years

All of this is general. In real life, situations force you to choose. For example, I had a friend who was much older than I was, and when I met her for the first time I naturally addressed her as vous (you use vous with someone older than you and whom you don’t know). Over the years (30 years of friendship!) and with affection, tu could have replaced vous, but that never happened.

We continued to say vous, which did not at all remove the affection, and for me it even marked an extra way of showing her respect in addition to friendship. Feelings, then, expressed by the choice between vous and tu without ever having to say them to the person. There was no need: the French language did the work.

Using “vous” with someone is sometimes a different way of loving them.

What “vous” allows: honoring someone

You can use ‘tu’ with someone older, but it's up to them to tell you. Obviously, if they're family, it's “tu.” Image par Besno Pile de Pixabay

You know, vous can be used to highlight someone. When you use vous with a teacher, a doctor, or an older person, you are saying: “I recognize who you are, what you have lived, what you know.” It is not inferiority. It is recognition.

What “vous” allows: honoring someone — and verbal protection

And sometimes, vous protects. It allows two people to remain in a kind, respectful exchange without intrusion. In a tense situation with someone you do not know, it helps show that you remain in a “civilized” relationship. In a way, it acts as a verbal dam against rising violence.

When someone is angry and switches to tu with a person they do not know, it means that anger has taken over, and that is not good at all.

In short, “vous” is not a barrier: it is politeness.

What “tu” can represent: fraternity

Tu says: “We are close.” Or even: “we are equals.” It removes the distance. It takes off the formal costume. It is a choice to be made. Often it happens naturally, because you feel comfortable with the person. But it also happens that one of the two feels obliged to ask whether you are going to use tu or vous.

That question is often received with pleasure, as a sign of respectful affection and an indication that the person asking to use tu likes you very much.

So you don’t necessarily start with tu, especially if you didn’t know each other before. Doing it from the beginning is like saying to the other person: “I am taking you without your consent.”

French people sense this immediately.

Two friends always use informal language with each other / Photo depositphotos

Real-life situations: when to say “tu” and when to say “vous”

Let me guide you as if you were living in France.

With a grandmother you don’t know:

→ you say “vous.”

Always.

With an office colleague:

→ it depends on the company culture.

In banking: “vous”.

In a start-up: “tu”.

With a waiter:

→ “vous”.

Out of respect, out of politeness.

With a doctor, or with a person who has a rank in general — a teacher, a lawyer, a judge, a police officer:

→ you say “vous”.

We always say “bonjour” or “bonjour messieurs dames” when we enter a small shop. Photo chosen by Monsieur de France: Ikonoklast via depositphotos

With a close friend:

→ “tu”.

With a stranger in the street:

→ “vous”.

With a friend of a friend whom you don’t know yet:

→ once you’re past 25 or 30 years old, and if you are the same age, start with “vous”.

Then you wait.

And if someone says to you:

“Oh, you can use tu with me!”

Then you go ahead.

The key phrase: “On peut se tutoyer ?”

This little sentence announces a warm moment. A gentle shift. A slide. It allows you to go “officially” from vous to tu and it signals budding affection.

It means:

“I’m opening the door to you.”

And:

“I trust you.”

When people say yes, they often smile.

It is a quiet, friendly victory.

At work, it depends on the place and the atmosphere. To begin with, at least with a superior, it is better to use the formal form of address Photo chosen by monsieurdefrance.com: opolja via depositphotos

How to be sure not to make a mistake

Here is the golden rule, the real one, the only one:

Start with “vous”.

Vous is noble.

Vous is safe.

Vous is elegant.

And if someone prefers “tu”, they will be the one to suggest it to you.

Typical mistakes foreigners make

The most common mistake is using tu too early. It may seem friendly in their culture, but in France it creates the feeling that the relational space is being pushed too fast. That said, French people are used to this with English-speakers and will never really take offence. It will make them smile.

Another mistake:

when a French person uses tu, and the foreigner continues to use vous out of shyness. It’s not serious, but it can create an asymmetry. If someone uses tu with you, the best thing is to use tu as well — but it’s up to you: you have every right to prefer keeping vous.

A third mistake:

thinking that using vous is cold. It is not. “Vous” can be tender. It is a tu dressed in a suit and tie.

A bit of history: from royal “vous” to revolutionary “tu”

During the French Revolution, “tu” was mandatory / Image chosen by Monsieur de France: By Jean-Baptiste Lesueur (1749-1826) - https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/plantation-d-un-arbre-de-la-liberte, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4266237

In the past in France, vous was truly the pronoun of majesty. People said vous to the king, of course, but also to all the nobility and more broadly to all high-ranking people. Vous created a respectful, almost ceremonial distance between the person speaking and the person being addressed.

When the French Revolution broke out, it tried to overturn these codes. The revolutionaries wanted to establish tu between citizens, as a symbol of equality. Calling someone tu was a way of saying: we are of the same rank, of the same people, on the same level.

But once that period had passed, vous gradually returned to social life. Why? Because French society likes nuance. It needs nuance. Vous makes it possible to express respect without denying possible closeness.

Today in France, tu and vous coexist naturally. They live together in the language and in relationships. And it is from this balance — between familiarity and elegance — that our social culture is woven.

FAQ — "tu" or "vous" in French ?

Is it rude to say “tu” too quickly?

Yes, often.

It can seem intrusive, too familiar.

Can you use “vous” with someone you like?

Yes — and sometimes it is very beautiful.

Using vous can express discreet and deep affection.

How do I know when to switch to “tu”?

When the other person suggests it, or when tu appears naturally in the conversation.

Can you go back from “tu” to “vous”?

Yes — but it is rare.

It can mean creating distance, a hurt, or a change in the relationship.

And if I make a mistake?

Don’t worry.

French people are forgiving with foreigners.

Smile. Apologise if you want. The effort is always appreciated.

Conclusion: understanding France through “tu” and “vous”

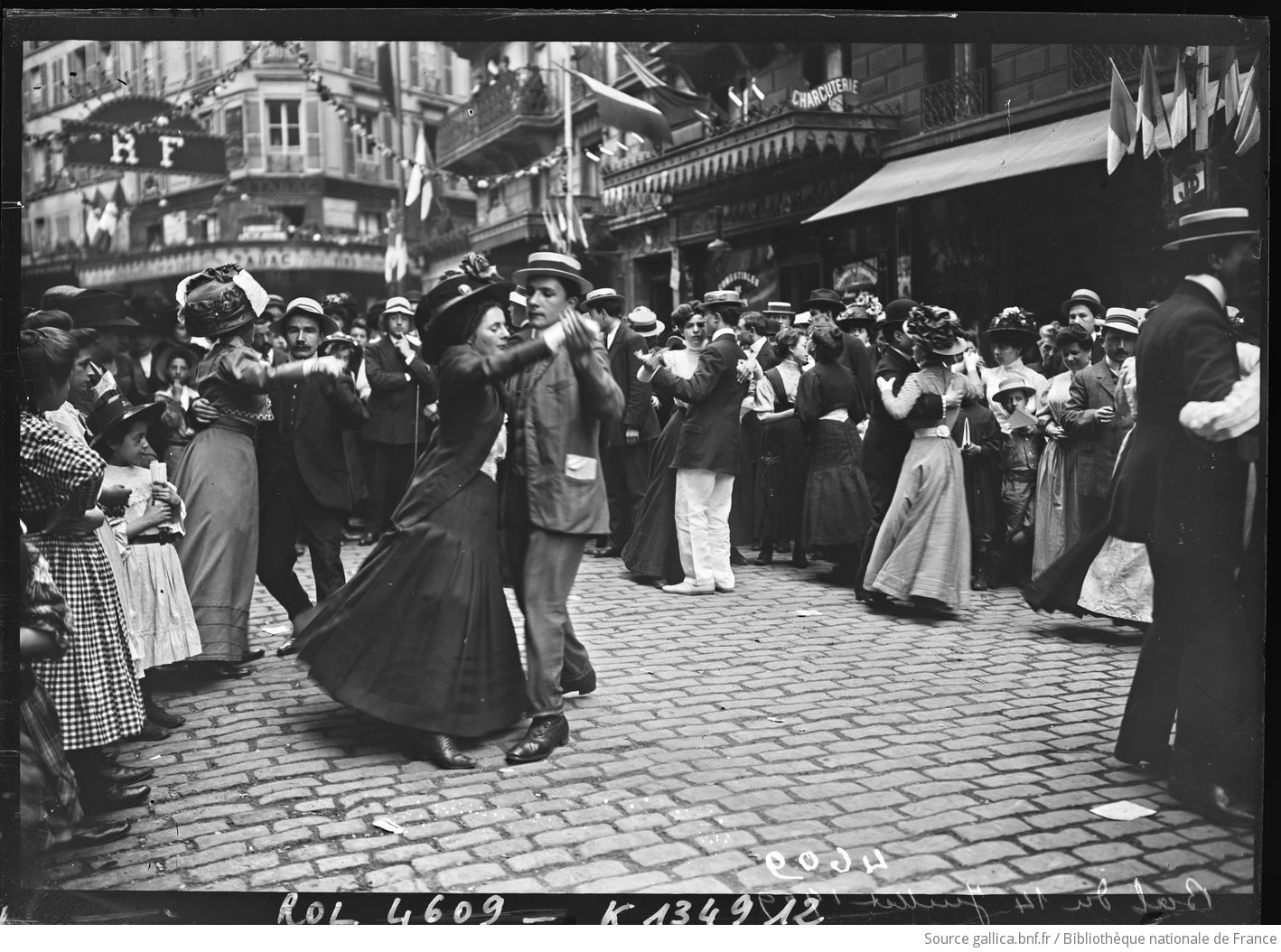

The July 14th 1909 ball in Paris. Source de Monsieurdefrance.com : Gallica.fr / BNF.

In the end, these two little words contain a lot of France.

They express our respect, our affection, our attention to the sensitivity of others.

They express that we do not step into someone’s world without being invited.

They express that closeness is something that is built over time.

If you master “tu” and “vous”, you are not just speaking French: you are beginning to understand France.

To learn more about the rules of politeness in France, click here. To learn about meal customs, click here.