Foie gras, more than “just liver”

If you simply translate the words, foie gras means “fat liver.” It sounds almost brutal. Yet when you taste it, you discover something very different: a silky, buttery, delicate product that melts on the tongue and leaves a long, elegant aftertaste. It does not taste like the strong, metallic liver many people know. It is milder, rounder, almost creamy. In France, foie gras is not everyday food. It belongs to the world of celebrations: Christmas, New Year’s Eve, weddings, big birthdays, family gatherings. For many French families, opening a jar or terrine of foie gras is like opening a special moment in time.

A festive table with champagne and foie gras / Photo selected by Monsieur de France: despositphotos

A very old story: from the Nile to Paris

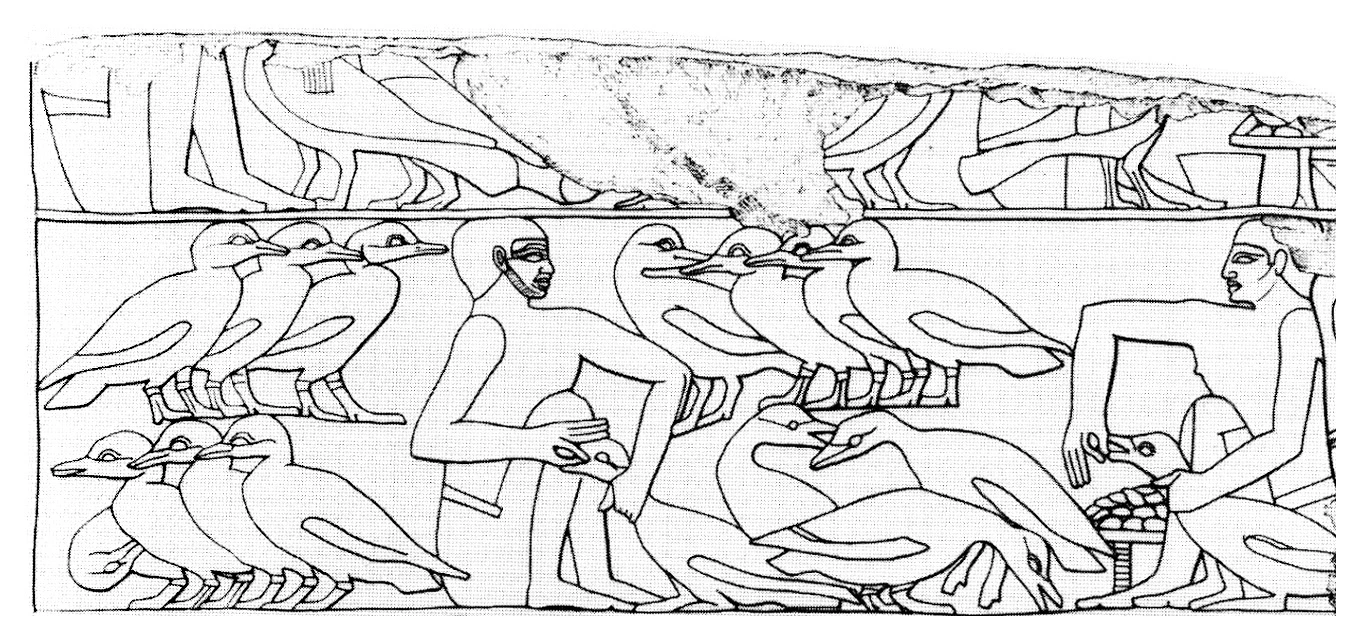

The story of foie gras does not begin in France, but on the banks of the Nile. The ancient Egyptians observed that wild geese naturally ate more before migration, storing fat in their livers. They started to encourage this process, and you can still see images of people feeding geese on ancient bas-reliefs.

The Egyptians already ate foie gras / Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=726386

The technique spread through the Mediterranean, adopted by Greeks and Romans, who served fattened goose liver at their banquets. Then history turned, empires fell, and many culinary traditions disappeared. But in some rural areas of Europe, people continued to raise geese and ducks, keeping the know-how alive. It was Marshal de Contades, governor of Alsace in the 18th century, who introduced foie gras to the court of Versailles and made it famous. It is said that Louis XVI was very fond of eating it. Centuries later, this heritage would meet French culinary genius.

Marshal de Contades discovered foie gras in Alsace and introduced it to Versailles / Portrait by unknown painter — Source unknown, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5153019

When France made foie gras part of its identity

Foie gras truly became a symbol of French gastronomy from the 17th century onward. In regions where geese and ducks were common, families used all parts of the animals. The liver, cooked and preserved in fat, became a prized treasure.

A beautiful view of the Château de Castelnaud in Périgord. Photo chosen by Monsieur de France: packshot via depositphotos.

Two regions especially embraced foie gras and refined it:

-

Alsace in the northeast, with a more delicate style, sometimes flavored with spices or sweet white wine.

-

Périgord and the Southwest, with a slightly more rustic, generous approach, often enriched with local spirits like Armagnac.

Over time, chefs in Paris and other cities took this rural product and brought it to the tables of palaces and grand restaurants. Foie gras became a bridge between farmhouse simplicity and high gastronomy, and that dual identity is still visible today: you can find foie gras both in luxury boutiques and in small countryside markets.

How foie gras is made (and why it is debated)

Foie gras comes from specially fattened ducks or geese. Traditionally, the birds are fed generously in the last weeks of their life so that their liver accumulates fat and develops its unique texture and taste. This process, known as gavage when done with a tube, is at the heart of modern debates. For many French producers and consumers, foie gras is a craft rooted in centuries of know-how; for critics, the practice raises questions about animal welfare. Some countries have restricted or banned the production, while in France foie gras is officially recognized as part of the national gastronomic and cultural heritage.

FreeProd via depositphotos

Knowing this context is important for visitors: it allows you to understand that foie gras is not a neutral product. It carries history, technique, pleasure – and discussion. Each traveler, of course, remains free to choose whether to taste it or not.

For my part, I only eat it at one time of year, during the holiday season. This allows me to limit my consumption and not increase the number of foie gras produced. What's more, something rare is much more precious than having it all year round.

The many faces of foie gras

When you walk into a French shop, the labels can be confusing. Here is what they mean in practice, from the traveler’s point of view:

-

Foie gras entier: whole or large pieces from a single liver, the most noble form.

-

Foie gras (without “entier”): pieces from several livers, assembled together.

-

Bloc de foie gras: a smooth, homogenized preparation, more uniform in texture.

-

Mi-cuit (semi-cooked): lightly cooked, sold in the fresh section, to be kept refrigerated; the texture is very soft and refined.

-

Canned or jarred foie gras: fully cooked and preserved, ideal to keep for months or to bring back home.

Terrine de foie gras / Photo choisie par Monsieur de France : depositphotos

If it is your first time, mi-cuit or canned foie gras from a good producer is often the easiest, safest option. You get the taste and texture without worrying about storage.

Wine Pairings: Sweet Whites and Champagne

Foie gras naturally pairs best with sweeter white wines, because their sweetness complements the fat richness of the liver instead of competing with it. A classic Sauternes or Monbazillac creates a perfect balance between sweetness and silkiness, amplifying the delicate, melting texture of foie gras. Alsatian late-harvest wines like Gewurztraminer are also excellent, with their honeyed and floral notes echoing the foie gras’ creaminess.

And just as importantly, foie gras pairs beautifully with champagne, especially brut or extra-brut. The crisp acidity and fine bubbles of champagne cut through the richness, refreshing the palate after each bite. This pairing feels elegant, festive, and unmistakably French, making it ideal for celebrations, holidays, and memorable meals.

Champagne ! Photo choisie par Monsieurdefrance.fr : KarepaStock/Shutterstock.fr

How the French really eat foie gras

There is a small ritual to foie gras in France. It usually appears at the beginning of the meal, before the main course, when everyone is still fully focused and hungry. The portion is small – just a few slices each – because it is rich.

The classic service is simple:

-

a few slices of foie gras, nicely arranged

-

good bread: country bread, baguette tradition, or sometimes brioche

-

maybe a tiny spoon of fig jam, onion confit, or fruit chutney

-

a glass of white wine (often sweet or slightly aromatic) or champagne

The idea is not to hide the foie gras, but to frame it. Bread is not there to dominate, but to support; the wine is not there to shout, but to accompany. And above all, the first bite should be pure: just foie gras and bread, nothing else.

Why I love foie gras (the intimate part)

Beyond history and technique, there is something more fragile: emotion. And that is where foie gras truly lives.

For someone who grew up with French festive meals, foie gras is more than a dish, it is a moment. I love foie gras because it is tied to memories of winter evenings, the glow of candles on the table, the clinking of glasses, the sound of a knife gently cutting the first slice while everyone falls quiet for a second. I love foie gras because it appears only on special occasions, and that rarity makes it precious. The first taste of the season, often around December, is almost a little ceremony: the bread is toasted, the plates are carefully prepared, somebody opens a bottle kept “for a good moment,” and for a few minutes the whole world seems to slow down.

Foie gras, for me, is the taste of time shared – time we decide to spend together, to talk, to laugh, to remember those who are not at the table anymore, and to celebrate those who are.

Duck or goose? Two personalities

In practice, most foie gras you will encounter in France is from duck. Duck foie gras has a slightly more pronounced, rustic character. Goose foie gras is often described as softer, more delicate, more buttery. It is also rarer and usually more expensive.

If it is your first time and you do not know which to choose, you can simply keep this in mind:

-

Duck foie gras: a little stronger, widely available, often slightly cheaper.

-

Goose foie gras: more subtle, smooth, associated historically with Alsace and festive tables.

There is no “right” answer. The best foie gras is the one that gives you pleasure when you taste it.

How to eat foie gras like a local (without making faux pas)

It's an art to pan-fry foie gras / Photo selected by Monsieur de France: depositphotos

French people rarely judge, but if you want to blend in, a few simple habits help:

-

Do not spread foie gras like butter. Place a slice on your bread, then take a bite.

-

Do not stack many things on top of it. A tiny bit of chutney is enough.

-

Avoid very strong pickles or spices that cover the taste completely.

-

Serve it cool, but never ice-cold; cold kills aromas.

-

Eat slowly. Foie gras is not something you “snack”; it is something you savour.

If you follow these small rules, you are already very close to the authentic French way.

Where to taste foie gras in France

A restaurant table: photo chosen by Monsieurdefrance.com: pitrs10 Depositphotos

One of the joys of traveling in France is discovering foie gras in different settings:

-

In Paris, you can try it in traditional brasseries, bistros, gourmet restaurants, and small delicatessens. Around Christmas, many food shops highlight their best foie gras in the window.

-

In Alsace, foie gras often appears alongside other festive dishes: you can taste it in winstubs (typical taverns), at Christmas markets, and from specialized producers.

-

In Périgord and the Southwest, foie gras is part of everyday pride. Local markets, farm inns, and village fairs offer tastings, and some farms organize visits so you can learn about their methods.

Wherever you are, the best advice remains simple: ask locals where they buy their foie gras. This question usually opens a smile, a story, and sometimes an invitation.

Bringing foie gras home

Many visitors want to take a bit of French celebration back with them. Canned or jarred foie gras is the most practical choice: it travels well and can be kept for months in a cupboard before opening.

Before you buy, check:

-

that the product is clearly labeled “foie gras”

-

that it comes from a known region or producer

-

your own country’s customs rules about animal products

Once at home, serving it is easy: chill the jar, open it gently, slice carefully, toast some good bread… and you are back at that French table, at least for a moment.

Foie gras, pleasure and moderation

No French person will tell you foie gras is a diet food. It is rich in fat and calories. But it is eaten in very small portions, once in a while. That is the French way: not to remove pleasure, but to frame it with moderation. A French person might have foie gras two or three times a year, perhaps a little more in the festive season. That is enough to keep it special. The idea is not to eat a lot, but to truly enjoy what you eat.

A cultural experience on a plate

For an international visitor, tasting foie gras is not an obligation. Some will be excited to try it; others will prefer not to, for personal or ethical reasons. Both attitudes are respected in modern France.But for those who do decide to taste it, foie gras offers a unique window into the French relationship with food, celebration, and memory. It shows how a simple product can concentrate history, technique, emotion, and debate in one small slice. In that sense, foie gras is almost like a French story you can eat: ancient roots, regional pride, family tradition, festive elegance, and just a touch of controversy. All in one bite.

FAQ – Everything you always wanted to know about foie gras

What exactly is foie gras?

Foie gras is the specially fattened liver of a duck or goose. It has a rich, buttery texture and a delicate, refined flavor that is very different from regular liver.

What does foie gras taste like?

Foie gras tastes smooth, silky, and mild, with a gentle, lingering aroma. It is rich but not aggressive, more like a savory butter than a typical organ meat.

Is foie gras the same as pâté?

No. Pâté is a general term for spreads made from meat or liver, often mixed with other ingredients. Foie gras refers specifically to the liver itself, prepared in a way that showcases its unique texture.

Why is foie gras controversial?

The traditional method of fattening ducks and geese, especially when it involves force-feeding, raises questions about animal welfare. Some people choose not to eat foie gras for ethical reasons.

Is foie gras legal in the United States?

Foie gras is legal in many parts of the US, but certain states or cities have restrictions or bans on its production or sale. It is always wise to check local regulations.

How do you serve foie gras properly?

Serve foie gras slightly chilled, in slices, with good bread or brioche. Start by tasting it plain, then add a little chutney or jam only if you wish. A glass of white wine or champagne pairs very well.

Should I choose duck or goose foie gras for my first taste?

Duck foie gras is easier to find and has a slightly stronger, rustic taste. Goose foie gras is more delicate and smooth. For a first experience, many visitors start with duck simply because it is more common.

Can I bring foie gras home from France?

Yes, many travelers buy canned or jarred foie gras as a souvenir. It usually travels well, but you must respect the customs rules of your own country about animal products.

Is foie gras healthy?

Foie gras is high in fat and calories, so it is a food to enjoy in small quantities and on special occasions. The pleasure comes from the quality of each bite, not from eating a large amount.

Do I have to like foie gras to “understand” French cuisine?

Not at all. Foie gras is an important symbol, but French cuisine is incredibly rich and varied. Even if you decide not to taste foie gras, you can still fully enjoy French gastronomy through cheeses, breads, pastries, seafood, regional dishes, and wines.