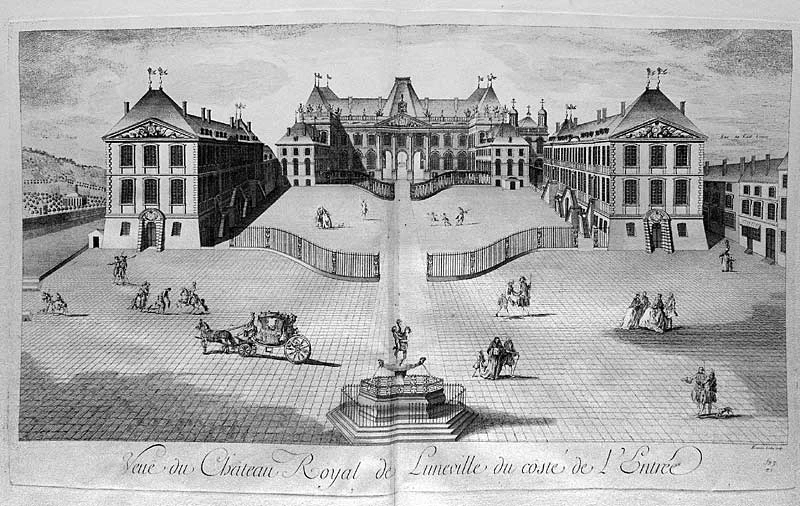

Why Lunéville Castle is nicknamed the Versailles of Lorraine

Lunéville Castle takes on incredible colors in the evening / Photo chosen by Monsieur de France: Leonid_Andronov

It is known as the "Versailles of Lorraine" for two reasons: it is enormous and it was built a few miles from the sovereign's official capital. But that is where the comparison ends. First of all, the castle and its symbols do not revolve around one man, as is the case with Louis XIV at Versailles. Here, the sovereign's bedroom is far from being the center of the residence, as it was located in the "ducal apartments," the duke's living quarters. And then, the castle reflects the character of the people of Lorraine: modest. Don't expect to find tons of gilding here. Firstly, the Duke of Lorraine was not as wealthy as the King of France, of course, but he was also an enemy of ostentation. The rare gilding serves to highlight one of the symbols of the dukes: the Cross of Lorraine, which can be found on the balconies.

Lunéville is immense yet modest. Don't expect to find the gilding of Versailles here. The gold leaf is not for the sovereign, but for Lorraine, which can be seen in the golden Lorraine crosses on the balconies. Photo selected by Monsieurdefrance.com / Jérôme Prod'homme

Origins: from a Gallic place of worship to the residence of the Dukes

Lunéville has very ancient origins. So much so that some grimoires claim that the site was a place of worship for the goddess of the moon in Gallic times. The site was fortified quite early on by the Counts of Lunéville, and it became part of Lorraine under Duke Mathieu II of Lorraine in 1243. Between 1620 and 1630, the old medieval castle was destroyed and replaced by a new castle at the behest of Duke Henri II of Lorraine and Bar (1563-1624). Badly damaged during the Thirty Years' War and abandoned by the dukes, who were forced to flee their estates occupied by Richelieu and Mazarin's France, Henri II's castle was also destroyed. In its place, Duke Leopold I of Lorraine and Bar decided to build his residence.

Leopold I and Germain Boffrand: the architectural genius of pink sandstone

Duke Leopold I "the Good" of Lorraine and Bar at around the age of 25, by Nicolas Dupuy. He is depicted with the attributes of sovereignty of his duchy: his cloak is lined with ermine (symbolizing sovereignty) and adorned with alerions (symbols of Lorraine), and the ducal crown placed near him is said to be "closed," reminding us that there is no one above him.

A 20-year-old duke with big ambitions:

Leopold I of Lorraine and Bar was born in Innsbruck, Austria, as the Dukes of Lorraine had been driven out by Louis XIII and Louis XIV of France in the 17th century. Louis XIV's reversals of fortune eventually forced him to accept the independence of the Duchy of Lorraine and the return of its hereditary ruler, the young 19-year-old duke. With the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697, Leopold regained possession of his duchies. He married Louis XIV's niece, the daughter of his brother "Monsieur," Elisabeth-Charlotte d'Orléans. The ducal couple made their entrance into a jubilant duchy and settled in Nancy, the capital. After 60 years of conflict, a terrible plague epidemic and a 17th century that had literally emptied it of its inhabitants, Lorraine finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel. Reconstruction began and, thanks to Leopold, the duchies of Lorraine and Bar entered one of the most glorious periods in their history: the 17th century.

Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte of Orleans. / Source: Wikicommons

And why not Lunéville?

Leopold liked Lunéville. He visited it occasionally and even undertook to renovate the Renaissance castle of his predecessor, Henry II. What finally convinced him to settle in Lunéville was the return of French soldiers to Lorraine in 1702 during the War of the Spanish Succession. Nancy, the capital, became the staging point for French troops on their way to war. Leopold refused to live in a place occupied by a foreign power. He chose to settle in Lunéville and build his residence there, befitting a sovereign prince.

The genius of architect Germain Boffrand

Presumed portrait of Germain Boffrand, architect of Lunéville Castle, by Jean II Restout

The duke called upon Germain Boffrand (1667-1754). Originally from Nantes, Boffrand was already renowned for his collaboration with Jules Hardouin-Mansart (to whom we owe the Grand Trianon and Place Vendôme), with whom he designed Place Vendôme. There were up to six different designs (so if you're building something, you're not the only ones who change their minds often!). The initial idea was an H-shaped plan with two large wings. The duke's finances prevented the second wing from being built. His finances also prevented him from building a chapel with marble columns, as in Versailles. It was Germain Boffrand who came up with a brilliant idea: pink sandstone columns, whitewashed, and a simple yet elegant sculpted plaster ceiling. The gardens were designed by Yves des Hours and completed in 1710.

Aerial view of Lunéville Castle and the Bosquets Park. The unfinished H shape is clearly visible. In front of the castle are two elongated buildings: the outbuildings, with the castle above them, and then the Bosquets Park. Image selected by Monsieurdefrance.com: aerial view via Google Earth.

The castle is preceded by two large buildings (the outbuildings) for the kitchens, horses, and servants. The right wing of the castle, a square surrounding a small interior garden, constitutes "the ducal apartments" in which the duke and duchess carry out both their official duties and their family life. A simple life, moreover, outside of official engagements. There are numerous descriptions that tell us of the apartments as a very lively and joyful place. In the fireplaces of their bedroom, the ducal couple's many children (they had 14) played, studied, and raised birds. The duchess did not disdain doing a little cooking in her room, particularly her specialty: pan-fried carp. In the castle, we meet Duchess Elisabeth-Charlotte, daughter of the Palatine and Monsieur, brother of King Louis XIV, Duke Leopold and his mistress Anne Marguerite de Ligniville, wife of the duke's best friend: Marc de Beauvau-Craon, whom the duke showers with gifts to thank him for turning a blind eye to his wife's love affairs... As a kind of family tradition, the Beauvau-Craon daughter will in turn become the mistress of the castle's sovereign, but not Leopold. We'll talk more about that later... Early in its history, the castle was struck by such a violent fire that the children were evacuated to the courtyard, where everyone waited in their nightclothes.

Lunéville Castle during the Age of Enlightenment. Source: Wikicommons

In 1729, the death of Leopold, the castle's builder, interrupted the work. His son, Francis III of Lorraine and Bar (1708-1765), lived in Vienna. In order to marry Maria Theresa of Austria (1717-1780), who would become Empress of Austria, and to become Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire under the name of Francis I, the young duke agreed to make an exchange with France, which refused him this marriage because it considered that if Lorraine became Austrian, it would be an Austrian gun permanently aimed at it. This diplomatic exchange was as follows: France agreed to the marriage of the heir to the Dukes of Lorraine to the heiress to the Austrian Empire. He became Grand Duke of Tuscany, replacing the last of the Medicis, who had just died. In exchange, in 1737, François agreed to give the duchies of Lorraine and Bar in perpetuity to Stanislas Leszczynski (1677-1766), former King of Poland and father-in-law of King Louis XV of France. It was agreed that upon Stanislas's death, Lorraine would be united with France. This would indeed happen upon Stanislas' death in 1766, after a reign of nearly 30 years...

Beauvau's wedding in 1721 at Lunéville Castle by Claude Jacquard (Musée Lorrain in Nancy).

The reign of Stanislas Leszczynski: Lunéville in the Age of Enlightenment

Stanislas Leszczynski (1677-1766), King of Poland, Duke of Lorraine and Bar for life. Portrait selected by Monsieurdefrance.com: Jean Baptiste Van Loo (Palace of Versailles).

Stanislas was twice king of Poland, and twice driven from the throne by the Russians and Saxons. He married his only daughter, Marie, to Louis XV, and it was to him that Lorraine was entrusted for life. He had no power whatsoever. Power, and the control of the people of Lorraine, were entrusted to a chancellor: Antoine Martin Chaumont de la Galaizière (1687-1783). Stanislas did not reign, but he was given a very comfortable civil list. He was a learned man, curious of mind, nearly 60 years old, who arrived in Nancy in 1737. He was eager to discover his new duchy. The fall was hard upon arrival, as his predecessor had left him absolutely no furniture. He even had the friezes removed from the roof of the Ducal Palace in Nancy. Stanislas was forced to sleep in the Beauvau family's mansion (now the Court of Appeal in Nancy) for a while, until the Château de Lunéville was ready for him. He moved there with his wife, Catherine Opalinska, who never went out because she had been told that the Lorraine climate was very bad for her health. The people of Lorraine were not at all favorable to him, considering him a usurper. In Commercy, which had been established as a principality for her, the Dowager Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte, wife of Leopold and niece of Louis XIV, took up residence in the Meuse castle and made no secret of the fact that she was absolutely opposed to her son's arrangement. Good-natured—he would be nicknamed "the benevolent"—Stanislas made the best of it. He quickly won people's hearts and, above all, made Lunéville the center of a dynamic, open, and welcoming court: the Court of Lunéville.

And he thinks big too

Although he had no real power, Stanislas still receives a very comfortable civil list (a kind of annual salary), which will allow him during his reign to build castles (the one in Einville au Jard, for example, was magnificent), the Notre Dame de Bonsecours church in Nancy, and, above all, the fabulous Place Stanislas. Lunéville was his residence, so he had many things built there, as he was a builder at heart. He had "folies" erected in the castle grounds. The clover, for example, was a pavilion where he could rest and smoke his "chibouque," a long pipe he had discovered while he was a prisoner of the Turks. In the castle, he enjoyed the "flying table" created by Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte, which allowed a table set in advance to be raised from the kitchens to the dining room so that he could serve himself without waiting and without servants (we will see that Stanislas was very, very greedy). Next to the park, above the river, he had "the rock" built, a series of tin figures, animated by water, which reproduced an ideal rural life. The figures moved, sometimes played music, amazed visitors, and Stanislas loved it.

The automatons of the Cour du Rocher at Lunéville Castle. Period engraving.

The golden age of Stanislas: when Lunéville lit up Europe

Marie Catherine de Beauvau-Craon, Marquise de Boufflers, Royal Mistress of Stanislas (1706–1786)

Curious and kind-hearted, Stanislas quickly surrounded himself with a court that rivaled Versailles and was much less stuffy. Among its members were the Marquise de Boufflers (1706-1786), the king's official mistress (which did not prevent her from looking elsewhere). A woman nicknamed "the lady of pleasure" who wrote her own epitaph: "Here lies, in deep peace, this lady of pleasure, who, for greater security, made her paradise in this world." For a time, she rubbed shoulders with Queen Catherine, the king's wife, which was quite remarkable in a castle that was large but where it was still possible to bump into each other. There we also meet "Panpan," François Antoine Devaux (1712-1796), a man from Lorraine who wrote poems and was the darling of the ladies of Lunéville. There was also an astonishing young man: Nicolas Ferry, nicknamed "Bébé" by the king. The court held parties for the Lorraine aristocracy, who still owned mansions in the sovereign's city of residence. Famous personalities were also welcomed.

Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet: love and science in Lunéville

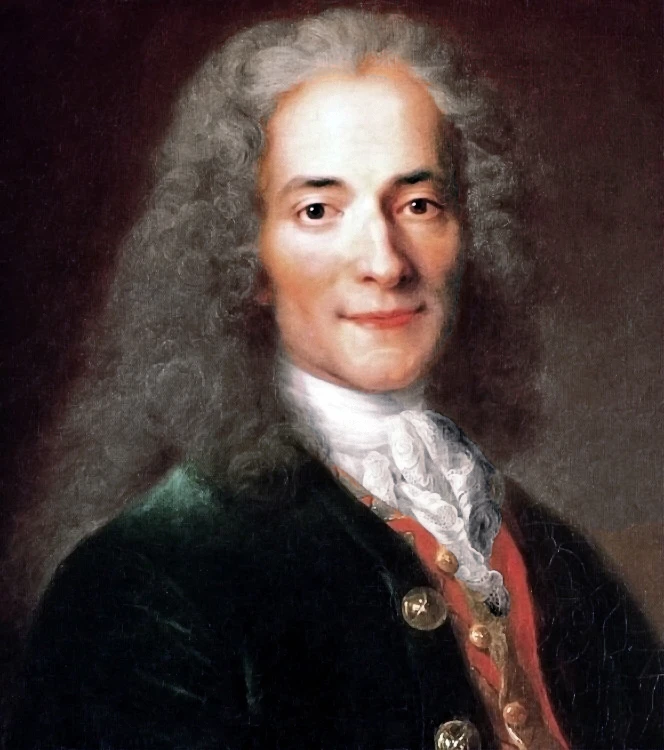

Voltaire (1694-1778) Wikicommones

Passionate about knowledge, a writer himself in his spare time (he left behind a considerable body of work in a "body of work by the benevolent philosopher," Stanislas liked to be called "the philosopher king." A practicing Catholic, he was open to his era and to the great minds of the 18th century, with whom he corresponded and whom he received regularly. This was particularly true of Voltaire (1694-1778), who liked Lunéville so much that he wrote, "it was almost as if we hadn't changed location when we moved from Versailles to Lunéville." He stayed there with the love of his life, the Marquise Emilie du Chatelet (1706-1749).

Emilie du Chatelet: learned woman and renowned mathematician

A woman of immense knowledge, she was the first female mathematician in French history. She translated Newton into French, adding comments that still make it a reference work today. A free-spirited woman, she embraced her identity at a time when this was not the case for everyone. She tragically ended her life in Lunéville in 1749.

Emilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Chatelet (1706–1749). Source: Wikipedia

In love with the Marquis de Saint Lambert (who is in love with the Marquise de Boufflers, Stanislas' mistress...), she becomes pregnant. She led her husband to believe that he was the father by inviting him to their castle in Cirey (an hour and a half from Lunéville today) and sleeping with him after getting him drunk (for the first time in years), then returning to Lunéville where she was due to give birth. The birth went wonderfully and a little girl was born. It was a few days later that she died after suddenly feeling unwell. Legend has it that this was after drinking a glass of too-cold orgeat syrup, but it was more likely an infection following childbirth. She still rests under a large black slab, with nothing engraved on it, at the entrance to the Church of Saint Jacques in Lunéville. Her death caused immense despair for Voltaire, who left Lunéville and eventually settled in Ferney, which became Ferney-Voltaire, not too far from Switzerland so that he could take refuge there if the King of France decided to imprison him because of his writings...

Did you know? The first "baby" in the history of the French language lived here.

The "baby dwarf" at the age of 11 dressed as a hussar (possibly by the Trubenbach workshop). Source: Wikicommons

He is a miniature man. At birth, Nicolas Ferry is so small that he sleeps in a clog. His parents present this strange child to King Stanislas, who offers to adopt him and take care of him. He had a small house built for him in the castle and a cart pulled by goats. He had him hide in a cake, from which he emerged armed and wearing a helmet while everyone was at the table, causing great commotion. His small size often played tricks on Bébé, who would get lost in the gardens, causing concern among the court. People are afraid of crushing Bébé, especially because the king often makes him hide under cushions to spray the ladies' behinds. Dying young (at the age of 25) of a broken heart, since he fell ill shortly after a miniature young woman refused his love, "Bébé" entered the annals of history for two reasons. He is the yellow dwarf in a board game (not a very nice dwarf, incidentally, reflecting Nicolas's bad temper) and, above all, because the nickname "Bébé" given to him by King Stanislas became a common name for a small child, a name that was transformed into "baby" in the English-speaking world.

The "baby dwarf" by Jean Girardet's workshops (1750). The dog allows for comparison. Source: Wikicommons.

An object of great curiosity in his day (he was nearly crushed by the Parisian crowd who wanted to see him and only escaped by managing to perch himself in the boot that served as a sign for a cobbler), Nicolas Ferry, known as "Baby," was studied by the naturalist Buffon, who preserved his skeleton, which is still on display at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris.

The tragic end of Stanislas and the union of Lorraine with France

Stanisław Leszczyński. Par Girardet. Source: Wikicommons

In February 1766, Stanislas was very old. He was over 88 years old and in very poor health. He could no longer see (and he insisted on fishing, so since he couldn't see anything, his servants would dive into the river to catch fish themselves, since the king couldn't see them, and he believed until his death that he was an excellent fisherman!). On this winter day, he is sitting by his fireplace, dressed in the beautiful dressing gown that his daughter, Marie, Queen of France, had sent him from Versailles. As he leans toward the fireplace to grab an ember and relight his pipe, he does not see that his dressing gown is too close to the hearth. It catches fire. Standing up and trying to extinguish the fire that engulfed his dressing gown, the king rose and ended up falling... into the fireplace. He was not found until much later, as no one had heard him, and his faithful servant was absent for the only time in years (he would never recover from this). After a week of suffering, Stanislas died, but not without a final touch of humor, as he looked at his mistress and his burns and said, "Madam! Did I have to burn with such a fire for you?" He was laid to rest in the Church of Notre Dame de Bonsecours in Nancy, which he had rebuilt for this purpose, alongside his wife Catherine Opalinska. Upon his death, the duchies of Lorraine and Bar were united with the French crown. Everything Stanislas had built was destroyed by order of Louis XV, including small buildings as well as castles. The castle of Lunéville became a kind of huge barracks. The great curtain of history fell on the Court of Lunéville.

Lunéville Castle during the cavalry regiment era in 1839 / engraving gallica.fr BNF website

From military barracks to rebirth after the 2003 fire

This did not ruin the town, which managed to bounce back and enjoy great prosperity throughout the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, as Lunéville was a sub-prefecture, a manufacturing center (faience in Lunéville Saint Clément, beaded embroidery, etc.) and industrial center, as it was there that the first French automobiles, the Lorraine Dietrich, were manufactured.

When Stanislas died in 1766, the tide of history turned abruptly for Lunéville. Stripped of its status as a royal residence, the castle lost its splendor. Louis XV, having no use for this distant court, ordered the destruction of several castles in Lorraine and transformed the "Versailles of Lorraine" into a huge military barracks. For more than two centuries, the hooves of cavalry regiments' horses echoed where the philosophers of the Enlightenment once debated. The castle became a defensive tool, housing thousands of soldiers, before gradually coming under the management of the department and the Ministry of Defense.

The tragedy of January 2, 2003

As the castle began its slow transformation into a cultural center, fate struck again. On January 2, 2003, a short circuit in the attic caused a fire of unprecedented violence. Fanned by storm winds, the fire devoured the roofs and historic framework and engulfed the ducal chapel. The residents of Lunéville watched helplessly and tearfully as their treasure was destroyed. The toll was heavy: a large part of the south wing was destroyed and irreplaceable decorations were reduced to ashes.

View of Lunéville Castle from the Cour d'honneur. At the top: the flag of Lorraine, emblem of the Dukes of Lorraine with three silver alerions / Photo selected by Monsieurdefrance.com: Traveller70/shutterstock.com

Europe's largest reconstruction project

But as so often in its history, Lunéville refused to die. Spurred on by a wave of national solidarity, the "Versailles of Lorraine" became the scene of a titanic construction project, the largest in Europe for a historic monument. Stonemasons, carpenters, and art restorers worked in shifts to bring the building back to life.

Today, the renaissance is spectacular. The pink sandstone facades have regained their luster, the roofs have been completed, and the chapel has been restored with surgical precision. More than just a restoration, it is a true resurrection that allows the castle to once again become the beating heart of Lorraine, now combining historical heritage and contemporary creation.

Stanislas, the gluttonous king

Stanislas was very, very greedy. Contemporaries recount that he ate very quickly, like a glutton, which did not suit his visitors, who had to eat as quickly as he did since they could not continue eating after the king; the table was cleared by the servants. He was particularly fond of melon, and was in fact responsible for the creation of the "Lunéville melon," a rather enormous melon, similar to a watermelon, which was grown on a large scale in Lunéville for many years and which frequently gave him indigestion. He was very fond of meat broth, which he ate for breakfast. And we owe at least two wonderful French specialties to Stanislas: the madeleine and the rum baba.

The madeleine

We owe the invention of this delicious biscuit to Madeleine, the maid, who improvised it one evening when Stanislas unexpectedly arrived at the Château de Commercy (the twin of Lunéville).

shutterstock

Rum baba

We owe the idea of baba to Stanislas. Very old (he died at nearly 90 years of age) and having lost all his teeth, he had gotten into the habit of moistening his brioche with wine to soften it.

I'll tell you the story and give you the recipe below.

depositphotos

In conclusion

Lunéville Castle is not just a stone monument; it is a vibrant testament to the spirit of Lorraine, capable of rising from the ashes as it proved after the tragedy of 2003. As you stroll through its gardens or admire the elegance of its chapel, you are walking in the footsteps of visionary rulers and geniuses of the Enlightenment who shaped France's cultural identity.

Today, this heritage extends far beyond the ramparts. Whether through the splendor of the nearby Place Stanislas or the sweetness of a madeleine fresh out of the oven, the soul of Lunéville continues to shine. To continue this journey through time and culinary delights, I invite you to explore the other treasures of our region.

Jérôme Prod'homme Specialist in French heritage, gastronomy, and tourism. Find all my discoveries at monsieur-de-france.com.

To go further:

-

Heritage: Visit Nancy, the capital of the Dukes of Lorraine.

-

Gastronomy: Discover the true story of Stanislas' Madeleine.

-

Practical Guide: Plan your visit to Lunéville: our top recommendations.

Frequently asked questions about the history of Lunéville Castle

Who designed the Château de Lunéville?

The current castle is the work of Germain Boffrand (1667-1754). This brilliant architect, a student of Jules Hardouin-Mansart, successfully adapted the codes of French classicism to the more modest means of the Dukes of Lorraine, notably by using the superb pink sandstone from the Vosges mountains.

Why did King Stanislas settle in Lunéville?

The former King of Poland, who became Duke of Lorraine for life, chose Lunéville as his main residence because his predecessor, Leopold I, had already built a modern palace there. Stanislas established a brilliant and cosmopolitan court there, making the city a true capital of the Enlightenment.

What caused the 2003 fire at the castle?

The terrible fire on January 2, 2003, was caused by an electrical short circuit in the attic of the south wing. The fire, fanned by strong winds, destroyed almost the entire roof and the priceless decorations of the ducal chapel.

Why is the castle nicknamed the "Versailles of Lorraine"?

This nickname comes from its imposing size, its classical architecture, and its function: a sovereign's palace located away from the capital (Nancy), just as Versailles is from Paris. However, Lunéville stands out for its greater simplicity and the absence of the ostentatious gilding typical of the Louis XIV style.

Illustrative photo: Leonid Andrinov via depositphotos